On the morning of August 2, 216 B.C., the largest Roman army ever assembled during the Second Punic War prepared for a decisive battle on the dusty plain of Cannae in southeastern Italy. The battle that followed would rock Rome to its core!

The Second Punic War was in its third year, and thus far for the Romans it had been a catalog of unmitigated disaster. They faced an enemy who had destroyed two Roman armies on Italian soil in as many years, wounding one Consul of Rome and killing another. This deadly foe was Hannibal Barca, chief general and leading statesman of the Carthaginian Empire.

In 216 BC the Roman Senate took the extraordinary step of raising a massive army of eight Roman legions, and an equal number of Italian allied legions. This was an extraordinary step; but these were extraordinary times.

The Senate determined to bring eight legions into the field, which had never been done at Rome before, each legion consisting of five thousand men besides allies…. Of allies, the number in each legion is the same as that of the citizens, but of the horse three times as great…Most of their wars are decided by one consul and two legions, with their quota of allies; and they rarely employ all four at one time and on one service. But on this occasion, so great was the alarm and terror of what would happen, they resolved to bring not only four but eight legions into the field.[1]

Commanding this mighty force were both of the elected Consuls for that year: Lucius Aemilius Paullus and his junior colleague, Gaius Terentius Varro. It was unusual for both Consuls to operate in the same theater of war, much less the same battlefield. But this was a sign of just how desperate the Senate was to bring Hannibal to a final, decisive battle, and end his rampage through Italy.

When war had been declared by the Senate of Rome against its bitter rival, Carthage, it was expected that this conflict would follow the same victorious course that the First Punic War had taken a generation before. Namely, that Roman fleets would sweep the sea of Punic opposition, clearing the way for Roman armies to land in Africa, and to fight the war on Carthaginian soil. After all, under the terms of the peace treaty that had ended that first conflict, Carthage had been barred from rebuilding its once proud fleet. It could in no way compete with Rome at sea, nor impede the transport of Roman armies to Africa. It was a given that in a clash on land, no Carthaginian army could stand before the legions of Rome and her Italian allies. Once in Africa, any Carthaginian army would be quickly defeated and the city placed under siege, its demise just a matter of time.

But Hannibal had other ideas.

Hannibal Barca (Hannibal, “Grace of Baal”, and Barca, “Thunderbolt”) was the son of Hamilcar Barca, the most successful Carthaginian general in the otherwise stunningly unsuccessful First Punic War. Hannibal had grown to manhood in his father’s camp, surrounded by soldiers. He had learned well the lessons his capable father had taught him. One of these was an undying hatred for their Roman enemies. Upon a sacred alter, the sons of Hamilcar had all sworn an oath to bring destruction to Rome.[2]

Hannibal Barca (Hannibal, “Grace of Baal”, and Barca, “Thunderbolt”) was the son of Hamilcar Barca, the most successful Carthaginian general in the otherwise stunningly unsuccessful First Punic War. Hannibal had grown to manhood in his father’s camp, surrounded by soldiers. He had learned well the lessons his capable father had taught him. One of these was an undying hatred for their Roman enemies. Upon a sacred alter, the sons of Hamilcar had all sworn an oath to bring destruction to Rome.[2]

Hannibal took command of his late father’s Army in Spain at the age of 26. Now, five years later, he had fulfilled the elder Barca’s wishes, taking the war to the enemy and visiting woe upon the Romans. At the outbreak of hostilities in 219 BC, Hannibal had seized the initiative, leading an army from his base in Spain across the wild, barbarous lands of the savage Gauls. Against all odds he had succeeded in crossing the snow-covered Alps, to debouch into the plains of northern Italy.[3]

Hannibal leads his bodyguard cavalry, supported by elephants, through a Celtic ambush in the Alps

There he had defeated the Roman forces that attempted to intercept and halt his invasion. First in a cavalry skirmish at the Ticinus River, where one of the Consuls for that year, Publius Cornelius Scipio (father of Africanus) had been badly wounded; and then at the River Trebia, where he inflicted a major defeat upon a Roman Consular army led by Scipio’s colleague, the Consul Sempronius Longus. After these victories, the Celtic tribesmen of the Po Valley rallied to the Carthaginian standard, joining forces with Hannibal and restoring his depleted numbers. The following year, Hannibal inflicted a third disaster upon Roman arms. At Lake Trasimene, the Consul Gaius Flaminius Nepos fell into a carefully prepared ambush and perished with most of his army along the fog-shrouded lake shore.

All Rome was stunned by these incredible events: two armies destroyed, a Consul slain, and an implacable enemy on their doorstep. Rome had suffered defeats before, but not since very early in the First Punic War had Roman arms suffered such humiliation[4].

After the disaster at Lake Trasimene the Senate turned the conduct of the war over to a temporary dictator, Quintus Fabius Maximus; who soon won the nickname of Cunctator (“The Delayer”). He had a different and decidedly “un-Roman” strategy in mind. Roman notions of generalship in the mid-Republic could be described as “Nelsonian”: no Consul could do much wrong who brought his legions to battle against the enemy. But three defeats in two years was quite enough to convince Fabius Maximus that something new was called for against this wily foe, who stratagems were characterized as “Punic treachery”.

After the disaster at Lake Trasimene the Senate turned the conduct of the war over to a temporary dictator, Quintus Fabius Maximus; who soon won the nickname of Cunctator (“The Delayer”). He had a different and decidedly “un-Roman” strategy in mind. Roman notions of generalship in the mid-Republic could be described as “Nelsonian”: no Consul could do much wrong who brought his legions to battle against the enemy. But three defeats in two years was quite enough to convince Fabius Maximus that something new was called for against this wily foe, who stratagems were characterized as “Punic treachery”.

During the rest of that year, 217 BC, Fabius kept his army just out of reach of Hannibal’s, hovering on the invader’s rear and flanks, all the while harassing and delaying the  Carthaginian’s progress through Italy. These tactics constrained Hannibal’s movements and demonstrated to the Italian allies that Hannibal was not free to march wherever he willed.

Carthaginian’s progress through Italy. These tactics constrained Hannibal’s movements and demonstrated to the Italian allies that Hannibal was not free to march wherever he willed.

But this “Fabian Strategy” of harassment and delay was too un-Roman for the hawks in the Senate. The more bellicose members clamored once more for a decisive confrontation on the battlefield. It was intolerable that an enemy army should defy Rome with impunity on Italian soil.

The following year, the Romans elected as one of the two Consuls Terentius Varro, an outspoken leader of the anti-Fabian faction in the Senate. Varro promised to bring Hannibal to battle and destroy him once-and-for-all. To accomplish this mission, the Senate gave both Consuls of 216, Varro and his colleague Lucius Aemilius Paullus permission to unite their forces into super-army, and crush Hannibal once-and-for-all.

Meanwhile, in the spring of 216 BC Hannibal’s army was in Apulia, where it had seized the large supply depot at Cannae. The historian Polybius notes that the capture of Cannae “caused great commotion in the Roman army; for it was not only the loss of the place and the stores in it that distressed them, but the fact that it commanded the surrounding district“. From here Hannibal could dominate the Apulian plains, harvesting grain to feed his troops and attempt to win-over the Italians of the district from their Roman alliance.

The consuls and their great army marched southward into Apulia to confront Hannibal. They found him camped on the left bank of the Aufidus River, near Cannae. After some initial minor skirmishing, the Romans set up camp nearby. Each day, command alternated from one Consul to the next. On the first day of August (a day after the Romans had set up camp) Hannibal deployed his army for battle. But Paullus, said by Polybius to be the more prudent of the two Roman commanders (see below), was supposedly loath to give battle on the plain against an enemy who had the advantage in cavalry.

Hannibal used his numerous cavalry to harass Roman foraging parties, particularly those bearing water from the river to their camp. In the hot Apulian summer this threat to their water supply was keenly felt. Feeling the shortage, on the following day the immense Roman army out of camp to face Hannibal on the plain. The Battle of Cannae was about to commence.

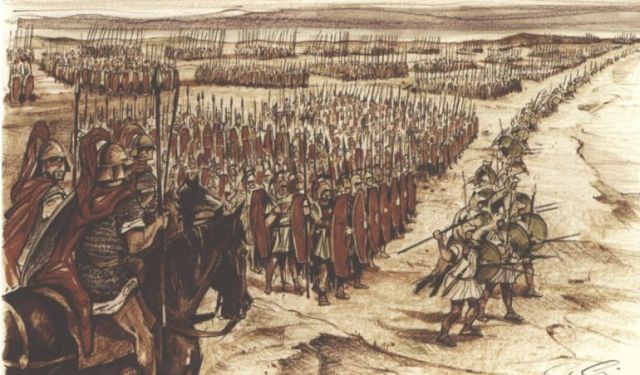

THE ARMIES DEPLOY

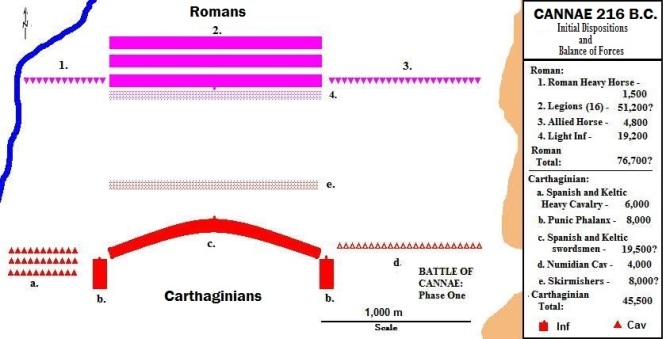

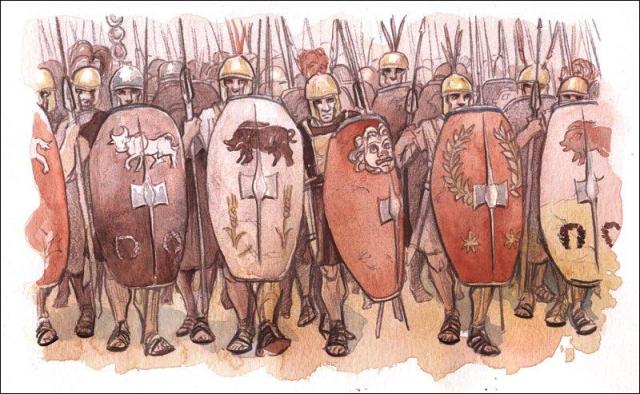

On the morning of the 2nd of August this massive double-Consular army, nearly 80,000 strong, deployed on the dusty plain near modern San Ferdinando. This battlefield was circumscribed by a river on one flank and low hills on the other. It was somewhat too narrow for so large a force to deploy with every legion (16 all together, half of which were Roman, the other half Italian allies) in its normal depth. For this reason, the legions were drawn-up in double the usual depth.

The Roman commander had every expectation of victory. He had noted a positive factor for the Romans at both their previous defeats (if anything positive could come from such disasters). At both Trebbia and Lake Trasimene the legions had been able to cut their way through the heart of the Carthaginian army. Though many had perished because of Hannibal’s devilish tricks, those survivors who’d escaped had done so the hard way: cutting their way through the center of the Carthaginian army. In each battle, though they had lost on the flanks, the Romans had won in the middle. It was obvious to Varro (or whoever planned the battle: see below) that the polyglot mercenaries who comprised Hannibal’s infantry could not stand before the hardy miles (soldiers) of Rome.

The plan, therefore, was a simple one: while the cavalry protected both flanks, the legions, drawn up in depth, would simply advance forward, shields held high and swords held low; and hack their way through the enemies center. The secret to Roman victory was what it had always been: attack!

The plan, therefore, was a simple one: while the cavalry protected both flanks, the legions, drawn up in depth, would simply advance forward, shields held high and swords held low; and hack their way through the enemies center. The secret to Roman victory was what it had always been: attack!

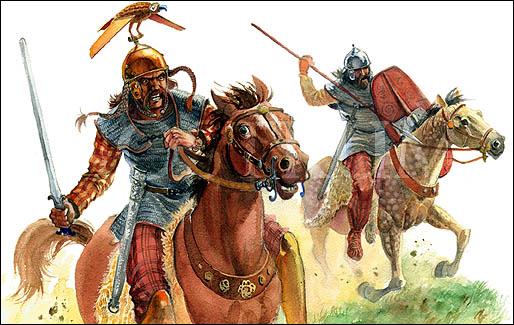

The Roman deployment that morning was likely observed by the one-eyed Hannibal with mixed trepidation and satisfaction. This was a much larger army than he had ever faced, twice the size of his own. However, he outnumbered the Romans in cavalry by the same proportion, nearly 2-1. His advantage in cavalry was qualitative as well. The Gallic and Spanish heavy horse had bested their Roman counter-parts in all the previous engagements; and in his Numidians he had perhaps the best light cavalry skirmishers in the western world.[5] In any case he was supremely confident in his ability to defeat the unimaginative Romans, for he had taken their measure in the previous battles. This day they appeared (to paraphrase Wellington) to be coming at him in the same old fashion; and he would beat them in the same old fashion[6]; though with a tactical twist all his own.

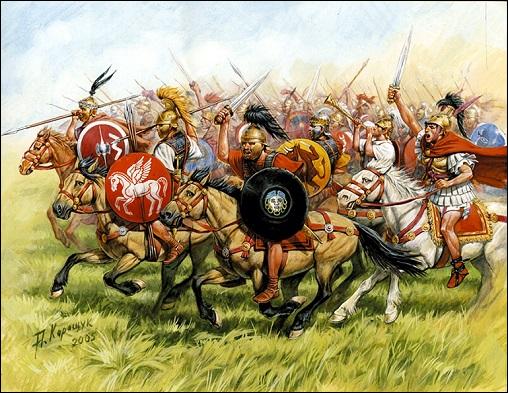

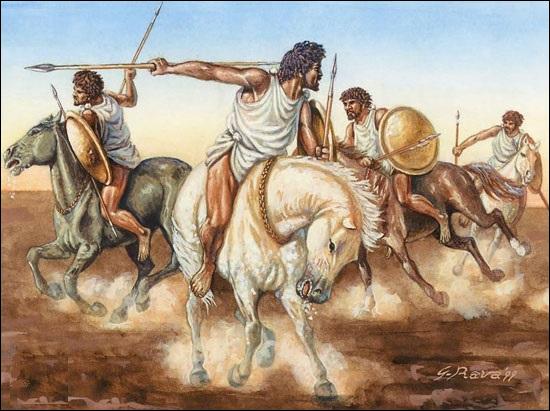

Hard-charging Celtic horsemen from the Po Valley of northern Italy were a key part of Hannibal’s heavy cavalry forces. These same Gallic horsemen later served the Romans well as auxilia in the centuries to come.

Hard-charging Celtic horsemen from the Po Valley of northern Italy were a key part of Hannibal’s heavy cavalry forces. These same Gallic horsemen later served the Romans well as auxilia in the centuries to come.

As Hannibal deployed his army he did so fully cognizant of the same facts upon which the Roman’s optimism was based: that in each of their previous engagements his Celtic and Spanish foot had proved unable to stop the Roman infantry. At both Trebia and Lake Trasimene, his infantry center unable to contain them, the Romans had cut their way out of a well-planned encirclement.

But Hannibal was a Barca, son of the brilliant Hamilcar. One of his favorite sayings was, “We will either find a way, or make one”. This problem of a “soft” center could be turned to his advantage. Like a martial artist, who uses his enemy’s weight against him, Hannibal now planned to pull off a brilliant piece of tactical ju jitsu.

As he drew up his battle line, Hannibal placed his veteran Spanish and Celtic infantry in the center. They would be hard-pressed, but he knew they could give a good accounting of themselves, slowing the Roman advance. Under pressure from the mass of pushing, stabbing legionaries they would surely be driven back and eventually broken. But instead of attempting to stand and hold, their orders that day were to slowly give ground, trading space for time. Time was what he needed, for the Romans to advance deeply into his center; and time for him to win the battle on the flanks, where his cavalry had all the advantages over their Roman counterparts.

He started by deploying his Spaniards and Celts in an arc, bulging forward in the middle towards the Romans. This both gave them more space to trade, and acted as a invitation to the Romans to attack here, in the center. It would appear as though he was massing his center, to thwart the expected Roman breakthrough. This, alone, would be a challenge the Romans could not refuse.

This odd deployment (the like of which was never again seen in any battle) gave the Romans no hint that Hannibal planned encirclement: were these his intentions, the Romans would expect to see his forces formed in a crescent, his center refused and his flanks advanced. His deployment, in-and-of-itself, was a piece of tactical deception.

Hannibal had one additional card to play in the center: behind each flank, concealed by the Spaniards and Celts, were his veteran Punic (or “African”) heavy infantry. These were men of mixed Libyan and Phoenician blood (often referred to as “Liby-Phoenicians” by modern writers). Their armament is a source of some controversy. Some writers have suggested that they carried the long Macedonian sarissa, a two-handed pike 5 to 7 meters in length. But Polybius refers to them as bearing the longche, which scholars agree was a light throwing spear. In some passages he describes them being used in the light infantry role; in other as heavy infantry (in pitched battles). They are indeed a conundrum. One possibility is that they were more akin to the Hellenistic “thorakitai“: hybrid troops, infantry who were armored and capable of fighting in the heavy infantry line when the occasion demanded. However, this is mere speculation and the truth is that we just don’t know.

These African Infantry were divided into two equal bodies, waiting behind each wing of his center. They would secure his infantry flanks, and wait in reserve for his signal: once the Romans became fully engaged with his Spaniards and Celts, they would advance on either flank and add their weight to the struggle.

But it would be up to his cavalry to win this battle.

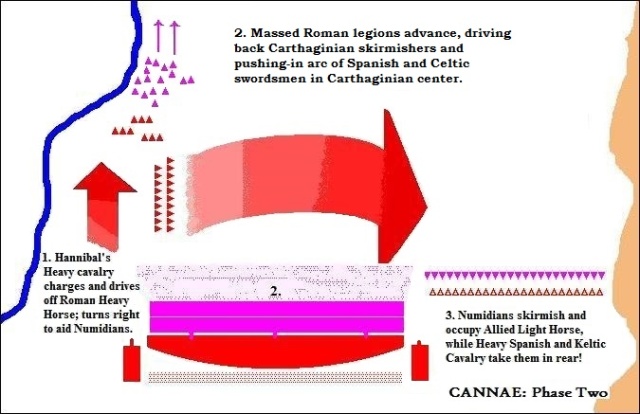

On his left, the river flank, Hannibal posted his 6,000 “heavy horse”. These were composed of Spanish and Celtic nobles, all good horseman and ferocious fighters. They would be facing a mere 1,500 Roman equites (wealthy horsemen of Rome’s upper classes).

Their mission was crucial: first to charge the equites and drive them from the field. This accomplished, they were to turn to their right and gallop for all they were worth behind the Roman army; and fall upon the rear of the Roman light horse on the opposite flank.

To keep these Roman light horse (provided by the Roman’s Italian allies) occupied, Hannibal opposed them with his 4,000 Numidian light horsemen. Their mission, like the infantry in the center, was to buy time for the heavy horse to win on the opposite side of the field; and come galloping to their aid. These small, swarthy men (from modern Algeria) riding swift ponies were among the best light cavalry in the Mediterranean, if not the western world. They rode without saddle, nor bit or bridle; guiding their mounts with just the pressure of their thighs.

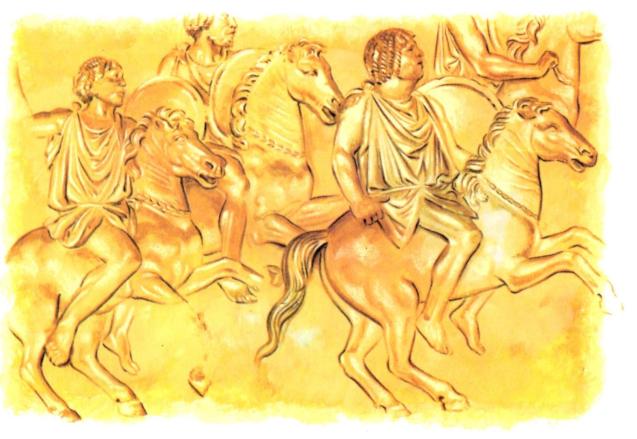

Image of Numidian light cavalry, from Trajan’s Column

Image of Numidian light cavalry, from Trajan’s Column

They wore no armor, and carried only a light hide-covered shield for protection. Their defense was their nimble handling of their swift ponies. That, and their deadly expertise with the javelins they carried as armament. Each man bore a bundle of these missiles; which they could either hurl with deadly effect, or retain in hand to fight at close quarters.

The Numidians would face the Varro’s 4,800 Italian light horse. Though these would outnumber his Numidians, they could be expected to skirmish with javelins rather than close and drive off the Numidians; thus playing into Hannibal’s plans. The Numidians had merely to keep their enemy occupied, exchanging missiles (and perhaps taunts) with their opponents.

Hannibal’s plan was as complicated as the Roman’s was simple. It was in many ways the same plan he had used to good effect at the Trebbia, but with the change in the center, where he had thrown in a new wrinkle; and with no troops waiting in ambush. His men knew their roles, and he was confident they could pull this off.

BATTLE BEGINS

When both forces had completed their deployment the battle began with the skirmishers advancing from each side into the “no man’s land” between the two armies. The Roman legions were screened by their velites, teenage boys in their first years of military service. They faced Hannibal’s Spanish and Moorish javelin-armed targeteers (so called because of the small round shields, called targe, that they carried), and by the Spanish slingers from the Balearic Islands. These skirmishers opened the battle by exchanging fire at range; while screening the advance of the heavy troops of the main battle lines from harassment.

Though less than a thousand in number, Hannibal’s Balearic slingers quickly dominated the skirmish battle. Natives of the Spanish Balearic Islands, they were highly prized in the ancient world for their expertise with the sling. It was said that no child among them was allowed his daily meat till he could kill it with his sling. They used smooth sea stones, slightly smaller than a golf ball. Some cast their ammunition out of lead, which flew faster and further. Whether stone or lead, these missiles delivered a deadly blow at considerable range: modern tests showing them capable of reaching out to 470 meters!

Though less than a thousand in number, Hannibal’s Balearic slingers quickly dominated the skirmish battle. Natives of the Spanish Balearic Islands, they were highly prized in the ancient world for their expertise with the sling. It was said that no child among them was allowed his daily meat till he could kill it with his sling. They used smooth sea stones, slightly smaller than a golf ball. Some cast their ammunition out of lead, which flew faster and further. Whether stone or lead, these missiles delivered a deadly blow at considerable range: modern tests showing them capable of reaching out to 470 meters!

The accounts of the battle (found in Polybius and Livy) make no mention of the effect of the numerous javelin-armed light troops on either side. But, immediately, the long range fire of the Balearics drove-in the Roman velites, forcing them to give ground, backing up into the ranks of the now advancing legions. The sling-shot now zipped into the ranks of the legionaries, causing casualties and goading these to hurry their advance in order to drive in these Balearic gadflies.

Roman Equites charging into battle. Usually capable heavy cavalry, at Cannae they inexplicably dismounted moments before engaging Hannibal’s heavy horse; condemning them to a swift defeat.

Roman Equites charging into battle. Usually capable heavy cavalry, at Cannae they inexplicably dismounted moments before engaging Hannibal’s heavy horse; condemning them to a swift defeat.

On the right of the Roman line, the goddess Fortuna smiled upon Hannibal. In one of those strange quirks of fate upon which the outcome of battle sometimes rests, a Balearic slinger’s missile struck the Consul Paullus, mounted at the head of the Roman equites. Paullus either fell from his horse, or dismounted in pain. Polybius tells that the staff officers around him also then dismounted to assist their fallen general. Perhaps seeing their commander and his staff dismounting, junior officers then ordered all of their men to follow suit; so at that minutes before going into action, all of the equites on the crucial Roman right flank inexplicably dismounted as well.

Hannibal, watching from across the battlefield, was astonished: mere moments before the oncoming cavalry clash, the Roman heavy cavalry were dismounting. A cavalry charge relies entirely upon the momentum and weight of horse and man. To receive a charge by dismounting was tantamount to suicide. “They might as well have delivered themselves up in chains”, he reportedly said.

Meanwhile in the center, goaded by the Balearic sling fire, the legions rapidly advanced towards the bulging Carthaginian center. Hannibal’s skirmishers skipped back through the ranks of his waiting heavy troops: their job, well done, now complete.

Both sides raised their war cries, and with a braying of horns and the bellowed commands of burly centurions, the legions charged forward. The Spanish and Celtic warriors raised their shields, and braced themselves for what was coming.

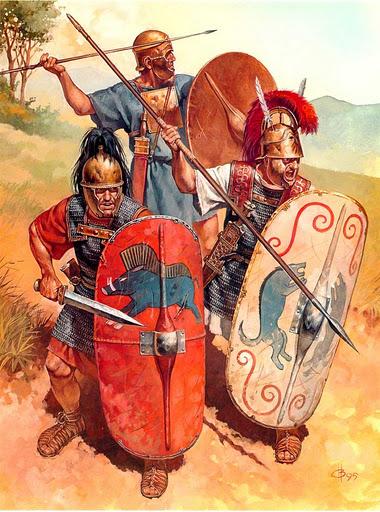

Into their ranks flew first one, then two flights of heavy-weighted pila, the anti-personnel harpoon carried by the Roman hastati (front-rank legionaries). Many front-rankers among the interspersed Spanish and Celtic companies must have been felled by these deadly missiles. Many more had their shields pieced, and if they couldn’t shake the pila off their shields were forced to throw them away and fight at great disadvantage with only with their swords.

They had no time for else, for mere seconds later the mass of Roman foot, heavy scuta tight to their shoulders, smashed into front of the bulging Carthaginian center. Immediately, the Spanish and Celtic warriors were forced back, one bloody step at a time. Though they planned to do so, there can be little doubt that pulling back while maintaining their order in the face of such pressure must have taken enormous effort, and a discipline unusual to any but the most experienced troops. It is a testament to Hannibal’s ability to motivate his soldiers that they held together and weren’t swept back in general rout. (It is perhaps to prevent this very thing that Hannibal placed himself behind his center, directing the effort and bolstering his veteran’s morale.)

Simultaneous to this clash in the center, along the river bank on Hannibal’s left the Carthaginian heavy horse charged into the dismounted Equites. As Hannibal predicted, dismounted as they were these had no chance. Though fighting desperately, trying to pull their enemies from their horses, the Romans were at a terrible disadvantage and were quickly routed from the field.

The scattering of the Roman heavy horse uncovered a gap between themselves and the rear of the advancing legions. Maharbal, commanding the Carthaginian cavalry, saw his opportunity. Like Cromwell at Naseby, leaving the front-line squadrons to pursue the broken Equites from the field and “keep the skeer up”[7]; he led the uncommitted rear squadrons through the gap to his right between cavalry and legions. Across the rear of the battle they galloped, to the opposite flank of the Roman army. Here, the Roman Allied light cavalry were locked in their own cavalry skirmish with Hannibal’s Numidians. Without pause, Maharbal’ squadrons charged into their unprotected rear.

Any battlefield, particularly in late summer, is a dusty place. Undoubtedly, in the midst of thousands of careening horses and tens of thousands of trampling foot-soldiers, the battlefield of Cannae became obscured by a vast cloud of dust. This explains why the progress of Maharbal’s horseman across the rear of the Roman army might well have gone unobserved by the Romans. His unexpected arrival in their rear struck the Allied cavalry like a thunderbolt from out of the blue. Shattered by this assault, the Roman light horse instantly broke and scattered in panicked flight.

Leaving the Numidians to keep up a steady pursuit and to prevent them rallying; Maharbal gathered his breathless squadrons together for the final phase of the battle.

Leaving the Numidians to keep up a steady pursuit and to prevent them rallying; Maharbal gathered his breathless squadrons together for the final phase of the battle.

THE BLOODY CLIMAX

Meanwhile, in the center, the battle was unfolding exactly as Hannibal had foreseen.

The legions had pushed back his convex center; first flattening it out into a line, then ever backward till it became a pocket, into which the legions were crowding. The Spaniards and Celts fought fiercely, desperate to hold on. But the line now threatened to buckle and break under the enormous pressure from over 50,000 pushing, heaving, and slashing legionaries.

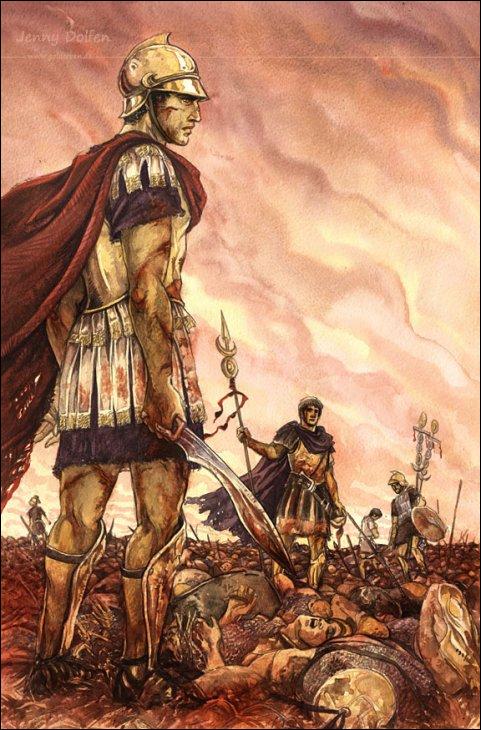

From Darkness Over Cannae (darknessovercannae.com); wonderful artwork by Jenny Dolfen

From Darkness Over Cannae (darknessovercannae.com); wonderful artwork by Jenny Dolfen

Wounded, the Consul Paullus had left the defeated and retreating right-wing horse. Knowing now that all hope of victory lay with the legions breaking the Carthaginian center, he rode back to join his infantry in the center. Dismounting, he threw himself into the fight, encouraging the men to press onward.

For Hannibal, the decisive moment had come. It was time to deliver the coup-de-grace. Seeing that the Romans in the center had pushed the line back beyond where the Punic heavy infantry columns waited to either flank he now ordered these to advance, turn inward, and form from column to phalanx! Pikes (or spears) leveled, these now pressed into the flanks of the Roman infantry.

At the same time Maharbal led his Celtic and Spanish heavy squadrons charging into the rear of the heavily engaged legions.

Attacked now from every side, the Romans had to fight in all directions. The pressure upon them relieved, the Spanish and Celtic warriors in the center pushed forward with fearsome war cries.

The chroniclers all agree that the press was now so great upon the trapped Roman infantry that the legions lost all order and cohesion. The normal three feet of space each man maintained from his neighbors, to allow each room to wield their weapons, collapsed as men found themselves pressed from all sides. Only those on the outer edge of the mass could fight; while those in the interior ranks were pressed so hard together that no man could raise his arms, even to lift their shields or swing their swords.

In the midst of choking dust and the din of savage war cries, the Roman army became a mob of terrified victims. Some, according to accounts, killed themselves where they stood, seeing that all hope was lost. Like pairing away the layers of an onion, the surrounding Carthaginians cut down rank-after-rank. The sheer enormity of the carnage argues that the bulk must have broke-and-run, and been cut down in the attempt.

For, as the day closed, the largest army Rome had hitherto fielded had utterly perished. Accounts vary, but somewhere between 50,000 and 60,000 died on that field. Another 10,000 became prisoners.. Hannibal released the non-Roman Italians among them. He did this for propaganda purposes, claiming he had come to fight Rome, not its Italian allies.

For, as the day closed, the largest army Rome had hitherto fielded had utterly perished. Accounts vary, but somewhere between 50,000 and 60,000 died on that field. Another 10,000 became prisoners.. Hannibal released the non-Roman Italians among them. He did this for propaganda purposes, claiming he had come to fight Rome, not its Italian allies.

The Consul Paullus died in the fighting, as did 80 other officers of Senatorial rank. Hannibal collected over 200 rings of members of the Senatorial class and sent them to Carthage as proof of the enormity of his victory. Varro, who commanded the Allied horse that day, escaped with them off the field.

CONCLUSION

Cannae was not the bloodiest defeat Rome would ever sustain (that was at Arausio, in 105 BC, against the Cimbri and Teutones). But it was the worst the Republic had experienced to date in their history. In true stoic fashion the Senate greeted the news of Cannae by issuing a proclamation forbidding public mourning. The following year new Roman armies, as well equipped as that which had perished, took the field and “soldiered on”, as though the loss had never occurred. That, ultimately, was the reason Rome triumphed in the end: her ability to sustain catastrophic losses without qualm or loss of resolve.

Tactically, Hannibal had pulled-off what would become the chimera for all future commanders: a double envelopment of a superior enemy force, and a subsequent battle of annihilation. The German General Staff, in the days of the Kaiser, studied Cannae obsessively. They considered this the epitome of tactical achievement, the blueprint for how a smaller army could defeat a larger. At Tannenburg, in East Prussia in 1914, they would put this study into practice, annihilating the advancing Russian Second Army.

Cannae was Hannibal’s masterpiece, and his last great battle in Italy. After this he was able to convince some of the southern Italian cities to open their gates to him, most notably Capua and Tarentum. But overall his goodwill campaign to win over the Italian allies of Rome failed. Though he continued to fight on in Italy for another thirteen years, the Romans avoided battle with him, hemming him in the south with several armies utilizing the tactics demonstrated first by Fabius Maximus.

Hannibal enters Capua in triumph after Cannae, riding his last remaining elephant

Meanwhile, Hannibal’s keenest student was Publius Cornelius Scipio, son of the Consul defeated at the Ticinus. Scipio had been present as a junior officer at Ticinus and at Cannae (at the latter he had led some 10,000 survivors from the field). In command of his own army in Spain, he developed his own lethal version of the double-envelopment to destroy Carthaginian armies in Spain; at first Baecula and then Ilipa.

While Hannibal was occupied in what had become a fruitless campaign in Italy, Scipio invaded Africa with a Roman army. Most of his legions were comprised of survivors of Cannae, men he had led off of that stricken field, seeking redemption. After Scipio destroyed the Carthaginian’s army of Africa at the Battle of the Great Plains, Hannibal was recalled to Africa by the Carthaginian senate. On the plains of Zama, the student would defeat the master; earning for himself the cognomen “Africanus”.

Scipio Africanus, Hannibal’s greatest student.

POST SCRIPT: WHITEWASHED NARRATIVE?

There is a problem with the accounts of Cannae, concerning which Consul was in command that day and therefore largely to blame for the disaster.

Most of what we know about Cannae (and the Second Punic War in general) comes from Polybius. Even Livy, writing during the reign of Augustus, and Plutarch a few generations later relied upon Polybius as their primary source for their accounts of the “Hannibalic War”. Polybius, in turn, did his research in the Scipio family library, being an intimate of that distinguished family. He was a friend and employed in the house of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, the conqueror of Macedonia and son of the Consul Paullus who fought at Cannae. Macedonicus entrusted Polybius with the education of his sons, Fabius and Scipio Aemilianus, who was an adopted member of the Scipio family.

This is germane because in writing his account of the battle Polybius seems to have white-washed the role of Paullus (his Roman benefactor’s father) and placed all the blame upon Varro. Our suspicion that all is not correct in the traditional narrative is based on three facts.

First, that Paullus took station on the right wing, and Varro on the left. The traditional place for an army commander in a Republican army of this period was on the right, the place of honor, commanding the Roman cavalry. Or, alternately and less commonly, from behind the center. But never on the left wing. The left-wing Allied cavalry would be commanded by the second-in-command, the “Master of Horse”. Though he claims that Varro was in command, Polybius and all later historians have Varro taking station with the Allied cavalry on the left, and his second-in-command, Paullus, taking the more authoritative station on the right.

Where a general stood in ancient armies was not merely symbolic. There was a good reason to be on the right-wing as opposed to the left. Most men are right-handed, and therefore their shields are on the left arms. War shields tend to be large, particularly the Roman scutum of the mid-Republic. Therefore, visibility to the left was limited by the shields of the soldiers and their mates to their left. However, visibility was far better to a soldier’s right. He could see his officers in that direction much more clearly than to his left. Also, because the right was the “shieldless side” it was more hazardous, and therefore where a general took station, exposing himself symbolically to the greatest risks.

For Varro to be in command and yet taking station with the non-Roman Allies seems passing strange, and out of the tradition of Roman military practice.

The second clue that all was not as Polybius would have us believe is found in the way Varro was received by the Senate after the defeat. While the surviving soldiers were disgraced and exiled to Sicily (where Scipio Africanus later recuited them for his invasion of Africa), Varro was welcomed back to Rome. There the Senate voted him thanks for “not despairing of the Republic.” Varro went on to a long and distinguished career in military and diplomatic posts.

Does this sound like the treatment meted out to a commander who had suffered what was, at that time, the worst defeat in the history of the Republic?

Finally, at Zama many years later Hannibal commented that he had faced not Varro, but Paullus, at Cannae. This is a strange thing to say, if in fact Paullus was only the second-in-command on that day.

All this suggests that Polybius, drawing on the Scipio family libraries, was fed the family “myth” that it was not his benefactor’s father that was to blame, but his “hot-headed” co-Consul, Varro. While we can never know at this point, there is reasonable grounds to suspect a whitewash.

NOTES:

- Polybius, The Histories; Book III: 107

- Ayrault Dodge, Theodore, Hannibal: A History of the Art of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans Down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 BC. (1995)

- See Breaching the Alps: Hannibal’s Icy Ordeal; Deadliest Blogger, May 30, 2017

- In 255 BC a Roman army under the Regulus was destroyed at the River Bagradas by the Carthaginian army commanded by a Spartan mercenary, Xanthippus. (This may be the same Xanthippus who a decade later commanded Ptolemaic forces successfully against the Seleucids in the Third Syrian War.)

- The Romans would soon recruit auxiliary cavalry from all of these peoples following the end of the Second Punic War, and continue to utilized the excellent services of these martial horsemen for centuries to come.

- “They came on in the same old way – and we defeated them in the same old way.” –The Duke of Wellington’s alleged, phlegmatic appraisal of the Battle of Waterloo.

- A favorite term used by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, to describe prolonged cavalry pursuit of a broken enemy.

(Thanks to Jenny Dolfen for granting permission to use her images. Visit her site for more: http://darknessovercannae.com/)

Some of the artwork in this article has been reproduced with the permission of Osprey Publishing, and is © Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

www.ospreypublishing.com

Thanks to the estimable Peter Connolly for the use of his amazing images.

Pingback: BLOOD IN THE DUST: CANNAE, HANNIBAL’S MASTERPIECE | Ritaroberts's Blog

Asolutely loved this post.. So well written and exciting to read. Thank you.

Thanks, Rita! I was wondering if you were still reading my pieces; hadn’t heard from you in a bit.

Hi Barry, I do read most of your posts but don’t always leave a comment. I did re-blog this one so hope that’s o.k. with you. I am in the middle of exams, plus have family here for two weeks of their holiday. I shall look forward to your next post..

Maybe you will enjoy thos post, I visited this special Exhibition near canbne last february: 🙂 https://verbavolantmonumentamanent.com/2017/02/09/annibale-un-viaggio-hannibal-a-journey/

It looks like a very well laid-out display.

It looks like a very well laid-out display.

Pingback: ADRIANOPLE: TWILIGHT OF THE LEGIONS | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: ELITE WARRIORS OF THE DARK AGES: VARANGIAN GUARD | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Awesome post, one of the best post that I had found about this battle, the PS about the whitewashing is great.

Glad you enjoyed it, Marco. Plenty more where that came from in the archives!

Pingback: MYRIOCEPHALON, 1176: BYZANTINE RESURGENCE COMES TO A DISASTROUS END | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Brilliant account of the battle. Thanks.

In defense of Paullus he did join the foot soldiers rather than running away with his defeated cavalry and fought to the death while Varro did a runner.

My understanding is that the Senate’s treatment of Varro differed markedly to their treatment of the soldiers who survived. They were literally sent to Coventry but later in a masterstroke, Scipio would recruit them for his African campaign and they would have their revenge at Zama.