The Battle of Brunanburh in 937 is mostly forgotten today, but it is a battle that deserves to be remembered. For it was the largest and bloodiest battle fought in Anglo-Saxon England prior to Hastings (and likely surpassing that later battle in the numbers of combatants involved). It left its victor, King Athelstan of Wessex the first Anglo-Saxon ruler to be called “King of England”.

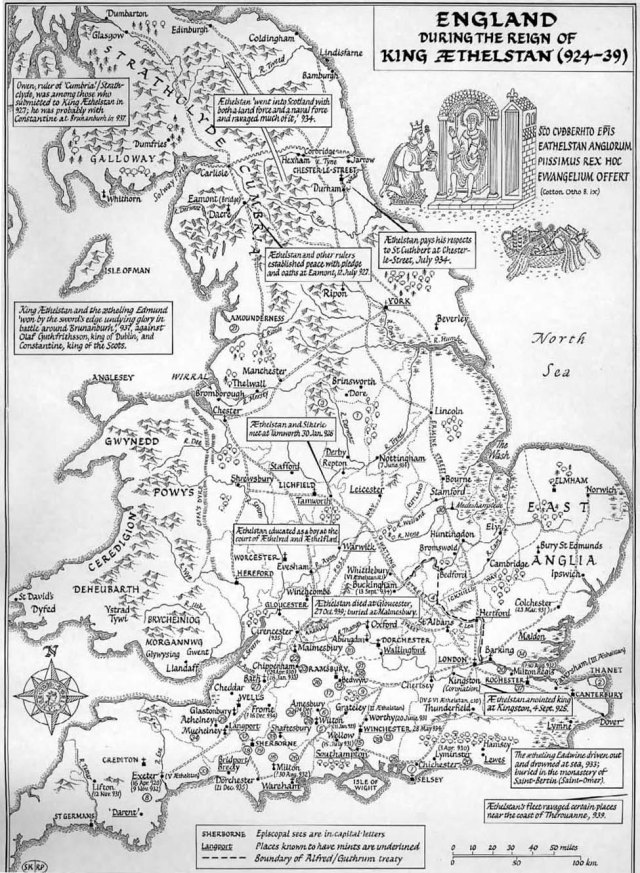

Athelstan was the son and heir of Edward the Elder, and grandson of Alfred the Great. Upon his father’s death in 924, Athelstan was acclaimed first King of Mercia (central England), and then on the following year King of Wessex (the dominant Anglo-Saxon kingdom, encompassing all the area south of the Thames). In 927, continuing the ambitious anti-Danish policies of his father and grandfather, Athelstan conquered York, which had been in Danish hands for 60 years; since captured by Ivar the Boneless and the “Great Heathen Army” in 867.

After this Constantine II of Alba (Scotland) and Owen I, ruler of British Strathclyde (Cumberland), submitted to Athelstan’s over-lordship. This effectively placed all of “England” under Saxon rule for the first time in history. (Prior to the Danish invasion of 866, England had been composed of four rival kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, and Wessex. The first three of these were Anglish; with Wessex the only Saxon kingdom.)

After seven years of peace Athelstan invaded Scottish territory. It has been suggested this was on account of Constantine’s attempt to renounce his submission to Athelstan’s over-lordship. A coalition was formed to oppose Wessex/English domination, which included the Hiberno-Scandinavian[1] ruler of Dublin, Olaf Guthfrithsson (called Anlaf in the Old-English poem “The Battle of Brunanburh“, possibly a great-grandson of Ivar the Boneless); as well as Owen of Strathclyde, and several “petty kings” and jarls joining Constantine of Alba in opposition to Athelstan.

Olaf crossed the Irish Sea with a Hiberno-Scandinavian army and marched through Cumberland, joined along the way by a force of Strathclyde British. In Northumberland they united their forces with that of Constantine’s Scots, along with various Danish jarls of northern England eagerly taking the opportunity to rise against their new Saxon overlord. This allied army met in battle the Northumbrian Fyrd (freeman-levy), commanded by Athelstan’s ealdorman, Gudrek and Alfgeir. The English were routed, with Gudrek slain. Alfgeir fled south to Athelstan, leaving Olaf and the allies in possession of Northumbria.

Olaf crossed the Irish Sea with a Hiberno-Scandinavian army and marched through Cumberland, joined along the way by a force of Strathclyde British. In Northumberland they united their forces with that of Constantine’s Scots, along with various Danish jarls of northern England eagerly taking the opportunity to rise against their new Saxon overlord. This allied army met in battle the Northumbrian Fyrd (freeman-levy), commanded by Athelstan’s ealdorman, Gudrek and Alfgeir. The English were routed, with Gudrek slain. Alfgeir fled south to Athelstan, leaving Olaf and the allies in possession of Northumbria.

Athelstan realized the enormity of the danger he faced, which threatened to undo all he had thus far achieved. He acted quickly, raising an equally large army from his lands in the south and hired Scandinavian mercenaries to strengthen his forces.

Athelstan’s army was comprised of the united fyrds of Wessex, East Anglia, and Mercia. These farmers and townsmen came armed with spear or axe and shield. They had little armor, but two generations of wars against the Danes had infused the English with a wealth of battle experience, and many were older veterans of earlier campaigns. Strengthening the fyrdmen were the professional warriors of Athelstan’s hearth-weru (“Hearth-troops”, or household guards) and the armed retainers of the leading ealdormen of the shires. Since the days of Alfred, such Saxon armies had stood toe-to-toe and bested one Viking army-after-another; and would have come to Brunanburh filled with confidence.

The numbers involved at Brunanburh are unknown, only that the armies were approximately the same size. Considering that this battle involved major forces from throughout the British Isles, with levies on either side drawn from as far afield as Ireland and Scotland, and all of England from the Cheviots to the Channel (and even a strong force of Viking mercenaries, primarily from Norway and Iceland) a figure of 15,000 per side seems reasonable.

The only complete account of this campaign and the climatic battle is found in the Icelandic Egils Saga. According to this source, a force of 300 veteran Norse/Icelander Vikings joined Athelstan’s guardsmen. These were led by two recently arrived Icelander brothers, the sons of Skallagrim (also referred to in the Saga as Skalla-Grímr, or “bald Grim”): Thorolf and Egil. It has been suggested that Athelstan hired several thousand such mercenaries, putting them all under the command of the experienced Skallagrimsson brothers.

The opposing forces met at a place called Brunanburh; or, according to Egils Saga, on a moor called Vin-heath. The location of the battle is not known for certain. But there are three leading contenders.

The opposing forces met at a place called Brunanburh; or, according to Egils Saga, on a moor called Vin-heath. The location of the battle is not known for certain. But there are three leading contenders.

The first, popular today, is Bromborough in western England district known as the Wirral, southwest of modern Liverpool. Apparently the name of Bromborough may be derived from Old English Brunanburh (meaning ‘Brun’s fort’). There are also locations nearby that some have attempted to identify with the Dingesmere, a place mentioned in both the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Old English poem, The Battle of Brunanburh, in connection with the battle. But this location in the Wirral seems too far southwest for a Scot and Strathclyde army to be operating, so far from their respective home bases (particularly as there were no good north-south roads connecting this area through Cumberland to Strathclyde and Scotland in the north). It also seems too far in the west to be the location for the decisive battle of a war fought over the control of Northumbria and Yorkshire, on the other (eastern) side of the Pennines.

The second contender is Burnley, a market town in Lancashire; where local folklore tells of a great battle on the moors. Local tradition holds that five kings were buried under tumuli on these same moors. Perhaps after the defeat of the Northumbrian ealdormen Olaf and the allies regrouped nearer their power centers in the north. But this makes little strategic sense. Having driven Athelstan’s forces out of Northumbria, why would the coalition army then pull out, marching back north? For the same reason, I dismiss another contender, Burnswark, situated near Lockerbie in Scotland.

The second contender is Burnley, a market town in Lancashire; where local folklore tells of a great battle on the moors. Local tradition holds that five kings were buried under tumuli on these same moors. Perhaps after the defeat of the Northumbrian ealdormen Olaf and the allies regrouped nearer their power centers in the north. But this makes little strategic sense. Having driven Athelstan’s forces out of Northumbria, why would the coalition army then pull out, marching back north? For the same reason, I dismiss another contender, Burnswark, situated near Lockerbie in Scotland.

A final, strong, choice for the battle site is in Lincolnshire, east of the Pennines, along the Great North Road between Derby and Rotherham. Historian Michael Wood suggests Tinsley Wood near Brinsworth as a plausible location. Wood notes that there is a hill nearby, White Hill, observing that the surrounding landscape fits the description of the battlefield contained in Egil’s Saga. Geographically this location makes the most sense. It is in the southern part of Northumbria, where one would expect the allies (who had recently overrun Northumbria) to contest with the English for control of that region.

Wherever the battle may have been fought, it seems that the opposing armies agreed to meet at Brunanburh, the winner to take all “England”. Egils Saga portrays this arrangement of a fixed battle as the result of a ruse posed by Athelstan’s Norse captain, Egil Skallagrimsson, to stop the allies from looting English territory while the King gathered his forces.

A challenge was issued to meet on a field “enhazelled”.

This was a version (writ large) of the Scandinavian dueling custom called a holmgang; in which combatants met to fight on an appointed field, the boundaries of which were marked out with hazel rods or branches. There is no other example I know of where this custom was expanded to encompass a battle between armies.

According to Egils Saga, a messenger was sent to Olaf challenging him to bring his army to meet Athelstan in battle:

…(they sent) messengers to King Olaf, giving out this as their errand, that king Athelstan would fain enhazel him a field and offer battle on Vin-heath by Vin-wood; meanwhile he would have them forbear to harry his land; but of the twain he should rule England who should conquer in the battle. He appointed a week hence for the conflict, and whichever first came on the ground should wait a week for the other. Now this was then the custom, that so soon as a king had enhazelled a field, it was a shameful act to harry before the battle was ended. Accordingly king Olaf halted and harried not, but waited till the appointed day, when he moved his army to Vin-heath.

King Olaf, commanding the allies, accepted the challenge. Accordingly, he halted his army at Brunanburh (which Egils Saga say was at Vin-heath by Vin-woods) and ceased ravaging the countryside about, waiting for Athelstan to arrive by the appointed day.

To the north of the heath, there was a village where Olaf made his headquarters. He sent a force of Scots and Strathclyde British commanded by two brothers, jarls Hring and Athils, up to the heath to camp on the prospective battleground and stake out the allied position. They found the hazel rods already in place along the edges of the field; and an English force camped in place to the south, commanded by the Skallagrimsson brothers.

As the appointed day for the battle approached King Athelstan was still gathering his forces and needed more time. He had sent Egil and his brother Thorolf, commanding the English vanguard composed of their own 300 Norse Vikings along with the remnants of the Northumbrian forces defeated earlier, under ealdorman Alfgeir, to Brunanburh. This was the force Hring and Athils found camped on the south end of the heath.

To make their numbers appear larger, the English disguised their small numbers by pitching more tents than they had need of, and arranged for a large portion of their men to occupy themselves outside the camp in view of the enemy as though the camp were over-flowing. When these were approached by Olaf’s men (there being a truce in place till the battle day), Athelstan’s men claimed that these tents were all full, so full that their people had to sleep out on the open heath!

When the appointed day of battle came Olaf marshaled his army and prepared to march onto the heath. Athelstan had yet to appear. Thorolf and Egil found yet another clever way of delaying the enemy and of buying the English more time: they sent an envoy to Olaf, feigning a message from King Athelstan; offering to avoid battle and pay “Danegeld” to Olaf and his allies.

Instead of attacking that day, Olaf called a conference of his allies to discuss the offer. Athelstan’s (supposed) offer was rejected as insufficient, and the allies countered with a demand for more. The English envoys begged for time to bring this offer to King Athelstan, who they claimed was a day’s journey to the south with a “mighty host”, and for their king to consider and respond. Olaf agreed to a further three days truce.

At the end of this period, the Skallagrimsson’s sent another envoy across the heath to Olaf’s camp, again claiming to be from King Athelstan. They offered the original amount; plus an additional “shilling to every freeborn man, a silver mark to every officer of a company of twelve men or more, a gold mark to every captain of a king’s guard, and five gold marks to every jarl”[2]. Again Olaf took this offer to a council of his allies, who after deliberation agreed that if Athelstan would also cede to Olaf the overlordship of Northumbria, the allies would withdraw to their homes. Another three days were granted for Olaf’s emissaries to accompany the English envoys back to Athelstan and await his answer.

At the end of this period, the Skallagrimsson’s sent another envoy across the heath to Olaf’s camp, again claiming to be from King Athelstan. They offered the original amount; plus an additional “shilling to every freeborn man, a silver mark to every officer of a company of twelve men or more, a gold mark to every captain of a king’s guard, and five gold marks to every jarl”[2]. Again Olaf took this offer to a council of his allies, who after deliberation agreed that if Athelstan would also cede to Olaf the overlordship of Northumbria, the allies would withdraw to their homes. Another three days were granted for Olaf’s emissaries to accompany the English envoys back to Athelstan and await his answer.

Thus the clever Skallagrimsson brothers, wily Viking freebooters, stretched out negotiations and gained the English monarch an additional week to marshal his forces. Athelstan arrived with his army south of the heath at the end of the period of truce. They took Olaf’s offer to the King, explaining their ruse and their offers on his behalf as well.

Athelstan took no time in rejecting Olaf’s terms, instead demanding that the coalition withdraw from Northumbria and return to their own lands, after returning the booty they had thus far taken on the campaign. Adding insult to injury, Athelstan further demanded that the cost of peace would be that Olaf (and perhaps the other coalition rulers) become his vassals, ruling their lands as “under-kings”.

“Go now back”, he told Olaf’s emissaries, “and tell him this.”

According to Egils Saga:

At once that same evening the messengers turned back on their way, and came to king Olaf about midnight; they then waked the king, and told him straightway the words of king Athelstan. The king instantly summoned his earls and other captains; he then caused the messengers to come and declare the issue of their errand and the words of Athelstan. But when this was made known before the soldiers, all with one mouth said that this was now before them, to prepare for battle.

Realizing he had been hoodwinked all along and now enraged, Olaf sent his jarls, Hring and Athils, back to their troops encamped on the heath with orders to attack the English advance guard under the wily Skallagrim brothers at first light. He promised to marshal the army and move to support them as soon as his forces were ready.

The battlefield at Brunanburh was set on a broad heath, or moor. It was bounded on the north and south by villages, which were the headquarters for each army. Which of these, if either, was called Brunanburh is unknown. The heath itself was level ground, bounded by a river on the west and the Vin-Wood to the east.

The battlefield at Brunanburh was set on a broad heath, or moor. It was bounded on the north and south by villages, which were the headquarters for each army. Which of these, if either, was called Brunanburh is unknown. The heath itself was level ground, bounded by a river on the west and the Vin-Wood to the east.

At first light, Hring and Athils led their men against the English vanguard of Norse and Northumbrians under the Skallagrimssons and Ealdorman Alfgeir, respectively. Egils Saga tells the tale thus:

As day dawned, Thorolf’s sentries saw the (enemy) army approaching. Then was a war-blast blown, and men donned their arms…they began to draw up the force, and they had two divisions. Earl Alfgeir commanded one division, and the standard was borne before him. In that division were his own followers, and also what force had been gathered from the countryside. It was a much larger force than that which followed Thorolf and Egil…. All their (the Skallagrimssons) men had Norwegian shields and Norwegian armor in every point; and in their division were all the Norsemen who were present.

The larger force of Northumbrians under Alfgeir took up a position on the left, their flank resting on the river. The Norsemen were on the higher ground beside the woods; and though the Saga is unclear on this, it seems likely that their was a gap between their two forces. The jarls Athils and Hring also drew up their force of Scots and Strathclyde Britons in two divisions, with Athils opposed to ealdorman Alfgeir on the lower ground, by the river, with Hring arrayed against the Norse Vikings on the high ground by the forest.

The opening act of the Battle of Brunanburh now began.

Both sides charged forward with spirit. Jarl Athils pressed the Northumbrians hard, forcing Alfgeir and his men to give ground. Before long the Northumbrians broke and Alfgeir fled, abandoning the Norse Vikings fighting beside them.

(This was the second time Alfgeir had abandoned a field in defeat. So sure he was of censure and punishment by Athelstan that he and his surviving followers avoided the king’s army and fled in disgrace south, into Wessex. From here, Alfgeir took ship to Frankia, where he had kin, never to return to England again.)

(This was the second time Alfgeir had abandoned a field in defeat. So sure he was of censure and punishment by Athelstan that he and his surviving followers avoided the king’s army and fled in disgrace south, into Wessex. From here, Alfgeir took ship to Frankia, where he had kin, never to return to England again.)

On the high-ground on the English right flank the Norse were holding their own against jarl Hring’s Strathclyde Britons. After pursuing Alfgeir’s Northumbrians for a distance, jarl Athils returned with his men to the field, coming up behind the Norse. Thorolf Skallagrimsson detached his brother Egil with half their troops and the standard, to turn about and fall upon Athils. Meanwhile he, Thorolf, pulled his remaining men back to the wood’s edge, forming a half circle with their wings resting on the woodline, where his men stood firm with their backs so protected.

Meanwhile Egil’s force charged against Adils’, and “they had a hard fight of it”, says the saga. “The odds of numbers were great (against them), yet more of Adils’ men fell than of Egil’s”. Still, the situation looked dire for the Athelstan’s Norse vanguard.

Egils Saga says that at this point Thorolf “became furious”. What is meant by this is unclear, but judging by what followed it seems to mean that Thorolf was overcome by what the Scandinavian sagas call “Berserkergang”: a furious battle-madness that lent the “berserk” a terrible strength and rendered him insensate to pain or fatigue. According to the sagas, berserks were “strong as bears or wild oxen, and killed people at a blow, but neither fire nor iron told upon them”. Its seems that Thorolf Skallagrimsson went “berserker”.

Throwing his shield onto his back, his “halberd” grasped with both hands, he raged forward against Hring’s troops, dealing cut and thrust on either side.

Thorolf’s weapon, as described in Egils Saga, is something of a mystery; matching no weapon described elsewhere in the sagas or in any account of Viking warfare: “(its) blade was two ells long (25”), ending in a four-edged spike; the blade was broad above, the socket both long and thick. The shaft stood just high enough for the hand to grasp the socket, and was remarkably thick. The socket fitted with iron prong on the shaft, which was also wound round with iron. Such weapons were called mail-piercers”. This could be simply describing a 5’-6’ great axe with a long spike at the end; but much of the description is open to interpretation.

Men sprang away from him both ways, but he slew many. Thus he cleared the way forward to earl Hring’s standard, and then nothing could stop him. He slew the man who bore the earl’s standard, and cut down the standard-pole. After that he lunged with his halberd at the earl’s breast, driving it right through mail-coat and body, so that it came out at the shoulders; and he lifted him up on the halberd over his head, and planted the butt-end in the ground. There on the weapon the earl breathed out his life in sight of all, both friends and foes. Then Thorolf drew his sword and dealt blows on either side, his men also charging. Many Britons and Scots fell, but some turned and fled.

With his brother Hring dead and his forces routed, the tide now turned against Athils. With his men falling around him or beginning to run away, he fled with those still fighting into the woods, where they were pursued for a short time by the Norse, who killed many before the rest escaped deep into the forest.

With his brother Hring dead and his forces routed, the tide now turned against Athils. With his men falling around him or beginning to run away, he fled with those still fighting into the woods, where they were pursued for a short time by the Norse, who killed many before the rest escaped deep into the forest.

Now both of the main armies came up onto the heath. But the day being late, they camped on the site where their mutual vanguards had been for the last week. Thorolf and Egil returned to camp, where Athelstan praised the Skallagrimsson’s for their victory in this first round of the conflict. They stayed the night together, pledging friendship.

King Olaf was apprised of the events on the heath that day, and that his jarls Hring and Athils were defeated, their men dead or scattered, and the former dead on the field. He must have spent the night with some trepidation, but prepared for battle the next day.

At dawn both armies deployed, their forces arrayed as on the first day in two wings.

Athelstan placed the bulk of his army around himself and his banner in the low ground beside the river, where rested his left flank; in the same place Alfgeir had occupied the day before. The saga says he placed the “smartest” companies in the van. This likely means that the better armed and armored household troops of the various ealdormen were in the front ranks; and the less experienced and poorly equipped fyrdmen behind them. There is no mention of where his own elite “Hearthmen” were stationed, but the Saga claims he asked Egil Skallagrimsson to command this mainbody, and the author of the Saga likely means that Egil was commanding the king’s Hearthmen. It is probable they formed the center of this division of the army, around the royal banner bearing the dragon of Wessex.

Athelstan placed the Norsemen, supported by other unspecified troops, again on the higher ground on the right, by the woods. These were commanded by Thorolf Skallagrimsson. They were to face the Scots, who fought as spearmen supported by a swarm of javelin-armed light skirmishers. Athelstan appreciated that the light-armed Scots were only dangerous to a foe that allowed his formation to break-up; and the king told Thorolf that he trusted the veteran Norse Vikings to maintain their tightly ordered shield wall.

When the king commanded these dispositions, Egil objected to being separated from his brother. But Thorolf quieted him, saying it should be as the king ordered. Filled with foreboding, Egil said, “Brother, you will have your way; but this separation I shall often rue.”

Olaf’s dispositions matched those of the English, with his own standard opposite that of Athelstan’s, his right flank on the river. His Hiberno-Scandinavian warriors, as well as the household troops of the various Northumbrian Danish Jarls would face Athelstan’s Saxon and English troops. As mentioned, Olaf’s Scottish allies faced Thorolf’s Vikings on the higher ground beside the Vin-wood.

Both armies (with the exception of the Scots) fought in much the same way: a dense line, many ranks deep, fighting close together with shields overlapping. This formation was called the “shieldburg”, or “shieldwall”. Warriors would strike at each other from over (or under) the rim of their shields, with spear, sword, and long-axe. Men in the second rank would support the first, holding their shields over their comrade’s heads; or, if armed with the long-hafted Danish battle-ax, strike from above at unprotected heads. Such a battle between two evenly matched and well-ordered shieldwalls was a bloody slug-fest; as men battled over or stepped upon a carpet of their own or enemy dead. One way of breaking such a formation quickly was the “swine-array”, a wedge-shaped formation meant to penetrate and shatter a shieldwall.

Drawing up armies of this size was an affair of hours, and it is unlikely the battle commenced before noon. The opposing armies closed with each other, hurling throwing axes and spears at their foes as they did. Then the walls of brightly-painted shields clashed together, and as the Saga says “the battle waxed fierce”.

On the right, Thorolf pressed eagerly forward along the edge of the woods, attempting to rapidly bend back and turn the flank of the Scots. Holding their linden wood shields before them, they brushed aside the barrage of light javelins the Scots hurled as they came on. Apparently, in his eagerness to get around the enemy’s flank, Thorolf ran far ahead of his followers. This was to prove his undoing.

At just this moment, out from the woods to Thorolf’s right, suddenly leapt jarl Athils and his surviving followers. It is not stated if they merely returned from deep in the wood, where they had taken refuge the day before, at an opportune time for the allies; or if this was an ambuscade planned in advance. But their sudden appearance caught Thorolf and his Norsemen by complete surprise.

Out ahead of his men, Thorolf found himself momentarily isolated, swarmed about and struck at from all sides. He was slain, and his men drew back. “The Scots shouted a shout of victory, as having slain the enemy’s chieftain.” With Athils’ followers they fell upon the leaderless Norse, and the struggle here grew desperate for Athelstan’s Vikings.

Out ahead of his men, Thorolf found himself momentarily isolated, swarmed about and struck at from all sides. He was slain, and his men drew back. “The Scots shouted a shout of victory, as having slain the enemy’s chieftain.” With Athils’ followers they fell upon the leaderless Norse, and the struggle here grew desperate for Athelstan’s Vikings.

From his position by the King’s banner Egil Skallagrimsson saw his brother’s banner pushed backward; and hearing the Scots triumphant shouting surmised his brother’s plight. He left his place and rushed to the right-wing, where he took command of his flagging Norse comrades.

With Egil in the van ferociously laying about him, the Norse (likely now formed in “swine-array”) hacked their way to Athils’ standard. The Saga says “few blows did they exchange” before Egil cut the northern jarl down, avenging his brother. Their leader slain, Athils’ men now broke and ran, the Norse close on their heals hacking at their backs. Nor did the Scots long stand, but seeing their Strathclyde allies flee likewise took to their heals.

To the west, the battle raged on the lower ground by the river, both shieldwalls locked in fierce struggle. Neither had the advantage, and many fell on both sides. Then, returning from pursuing the Scots, Egil and the Norse fell upon the rear of King Olaf’s division. The carnage was terrible, as Olaf’s warriors were struck down from behind. Seeing his enemy beginning to crumble, Athelstan ordered his standard forward, and the English line advanced with renewed fury.

The Hiberno-Scandinavian line disintegrated, and the Saga claims there was “great slaughter”. The casualty figures for either combatants are unknown, but many thousands died on both sides, and the coalition army was utterly routed. Here the Saga’s account of the battle ends, stating:

The Hiberno-Scandinavian line disintegrated, and the Saga claims there was “great slaughter”. The casualty figures for either combatants are unknown, but many thousands died on both sides, and the coalition army was utterly routed. Here the Saga’s account of the battle ends, stating:

King Olaf fell there, and the greater part of the force which he had had, for of those who turned to fly all who were overtaken were slain. Thus king Athelstan gained a signal victory.

But on the fate of Olaf Guthfrithsson Egils Saga is mistaken: Olaf escaped with at least a portion of his men, returning in defeat to Dublin.

However, the Saga is correct that Athelstan’s victory was indeed decisive. He had destroyed the coalition against him, and reasserted English control over Northumbria. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the deaths of five kings and seven jarls among his enemies. Among the slain was the Scottish king’s own son, cut down by Egil’s vengeful Norse. The Annals of Ulster agree:

Many thousands of Norsemen beyond number died although King Anlaf (Olaf) escaped with a few men. While a great number of the Saxons also fell on the other side, Æthelstan, king of the Saxons, was enriched by the great victory.

AFTERMATH

Athelstan had completed the work begun by his grandfather, Alfred: he had united all the former Anglo-Saxon kingdoms under the Dragon of Wessex; forced the Strathclyde British and the Scots into vassalage; and in the process turned back yet another attempt by Scandinavian forces to assert control of Northumbria.

After Athelstan’s death two years later, Olaf would return in 939 and force Athelstan’s successor, his brother Edmund, to cede Northumbria and part of Mercia. Thereafter, Hiberno-Scandinavian kings ruled Northumbria from York for decades (with the exiled Norwegian King, Eric Bloodaxe seizing and holding Northumbria twice during this period). Control of Northumbria would pass back-and-forth between English and Scandinavian rulers till after 1066, when England’s new Norman masters would finally bring the region under their control.

But in the years following his crowning victory at bloody Brunanburh Athelstan son of Edward had earned the right to style himself “Æthelstan, King over all Britain and Scotland” (totius rex Brittanniae et Albionis): the first “King of England”.

Tomb of Athelstan at Malmesbury

————————————————————————–

NOTES

1. Many authors refer to Olaf’s forces as Hiberno-Norse; or simple Norsemen. But as many, including Olaf himself, were of Danish extraction it is inaccurate to call them such. To avoid confusion with the Norsemen who followed Thorolf and Egil Skallagrimsson and fought with Athelstan, I refer to Olaf’s warriors as Hiberno-Scandinavian.

2. Egils Saga, Ch 52

RECOMMENDED READING

David Pilling is an excellent historical author, whose books I enjoy immensely. His series on the Arthurian Age in Britain is quite good, and I share most of his historical conclusions. Here is the first in that series:

Leader of Battles (I): Ambrosius (Historical Action Adventure)

Some of the artwork in this article has been reproduced with the permission of Osprey Publishing, and is © Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

www.ospreypublishing.com

Very interesting piece. I knew nothing of this why is English history not taught in schools well it wasn’t when I went

The quality of historical education is wretched.

Why no mention of the DORE STONE.?

The story mentions Tinsley which is now in the city of Sheffield,As is Dore which at that was a village. The first Overlord of all England was proclaimed there .A stone now stands there on the village green. Google it for a photo of it .

Pingback: Athelstan and Brunaburh | murreyandblue