“For the Spartans, it wasn’t walls or magnificent public buildings that made a city; it was their own ideals. In essence, Sparta was a city of the head and the heart. And it existed in its purest form in the disciplined march of a hoplite phalanx on their way to war!”

“For the Spartans, it wasn’t walls or magnificent public buildings that made a city; it was their own ideals. In essence, Sparta was a city of the head and the heart. And it existed in its purest form in the disciplined march of a hoplite phalanx on their way to war!”

– Bettany Hughes, writer/historian.

>

(It is highly recommended you first read Part Four; or, to start from the beginning, go here)

BRASIDAS’ NORTHERN CAMPAIGN

The Spartan commander Brasidas arrived in Macedonia at the head of a small Army of allies and freed (and trained) helot-hoplites, called neodamodes. His purpose was to break the Athenian’s hold on the northern Aegean coast; and, ultimately, to capture Byzantium, thus severing Athens’ vital grain supply from the Black Sea region.

Immediately, tensions developed between the Spartan general and his ally, the Macedonian king Perdiccas II.

Immediately, tensions developed between the Spartan general and his ally, the Macedonian king Perdiccas II.

Macedonia in the 5th century BC was not the united realm it would be under Philip II and Alexander. All of the western Macedonian highlands, so-called “Upper Macedonia“, were divided into semi-independent petty-kingdoms: Orestis, Pelagonia, Lyncestis, Eordea, and Elimeia . Macedonia proper, where the king’s writ was law, was confined to the great plain of the Axios River and the western foothills. Its coastal regions and the Chalcidice Peninsula were contested by the presence of independent Greek colonies who were subject-allies of the Athenian Empire.

A Macedonian national “army”, as such, did not yet exist. The sophisticated, combined-arms force Alexander led against Persia was the creation of his father Philip, and still some 70 years in the future. Perdiccas had nothing but his household cavalry and foot-guards, those nobles and their mounted retainers who chose to respond to a royal summons, and a poor-quality infantry militia of farmers and townsmen. The sarissa–armed phalanx was also a thing of the future. The Macedonian infantry of the day carried javelin. The nobility and the king’s retainers, collectively known as the “Companions” (hetairoi), were some of the best cavalry in Greece. But they were a relatively small force, numbering in the hundreds, not the thousands. While not yet the trained and well equipped cavalry regiments of Philip and Alexander, they had a reputation for excellence second only to the horsemen of Thessalia.

Perdiccas had allied with Sparta against their Athenian enemies in order to break Athenian power in the north; creating the opportunity for Macedonian expansion and control of the Macedonian coast. But upon the arrival of Brasidas and a Peloponnesian army he first demanded that his Spartan ally help him assert his authority over the highland kingdom of Lyncestis as a prelude to any campaign against the Athenians.

Brasidas had no interest in wasting time and manpower fighting Perdiccas’ private wars against his local rivals. Instead, he opened negotiations with the Lyncestians, offering himself as arbiter in their conflict with Perdiccas. Meanwhile, he marched his force into the Chalkidice to campaign against Athenian interests there.

Here his skill as a politician and (unusual for a Spartan) orator showed themselves. Proclaiming himself their liberator from Athenian domination Brasidas was able to exploit simmering resentment against Athenian high-handedness. First Acanthus, then Stagira submitted. By December he was welcomed at the Andrian colony of Argilus, and was threatening neighboring Amphipolis, the Athenian colony at the mouth of the Strymon River.

Amphipolis sent for help to the nearest Athenian force on the island of Thasos, commanded by the general Thucydides (the later historian). Thucydides rushed to the scene, landing at Eion, port of Amphipolis. Though able to garrison the port, he found learned that Amphipolis had surrendered on generous terms to Brasidas, whose army occupied the city.

The news of the loss of Amphipolis shook Athens, evoking an immediate reaction. Thucydides was (unjustly) blamed for not “saving” the city, and was dismissed and exiled. (Unable to serve his city in this, its greatest struggle, he resigned himself to faithfully chronicling the events; providing us with one of the best histories from the ancient world.) Meanwhile, one Chalcidician town after another now followed the example of Amphipolis and went over to the Spartans.

Thucydides

Thucydides

Panicked, the Athenians requested an armistice to discuss peace; something they had rejected after their humiliating victory at Pylos and Sphacteria (see Part Four). The Spartans, eager to see the return of the prisoners taken at Sphacteria, granted the Athenian’s request.

Meanwhile, the Chalcidice cities had thrown off their Athenian allegiance and requested Brasidas’ protection. Loath to give up the fruits of his victory at Amphipolis, or to leave these towns to the “mercy” of the Athenians, he granted their pleas, sending to Sparta for reinforcement to defend his gains.

The armistice broke down, and Athens dispatched the generals Nicias and Nicostratus with an army to restore their authority in the north. Mende was recaptured, and Scione besieged (though it held out). Brasidas, for his part, found himself isolated, as the Athenians closed off the land route through Thessaly to Spartan reinforcements had any been planned.

King Perdiccas, disappointed with Brasidas for liberating the Greek cities of the Chalcidice and not turning them over to him, demanded that his ally now assist him against the Lyncestians. This time Brasidas acquiesced, and joining forces with the Macedonian king marched into the highlands to the west.

Here, they found themselves outnumbered and hard pressed by the hillmen. Perdiccas, perhaps planning all along to get rid of his too-independent Spartan ally, now betrayed Brasidas and in the middle of the night withdrew his forces. Returning to lowland Macedon, he perfidiously changed sides, making peace with the Athenians.

Brasidas found himself in dire straits, outnumbered and surrounded by hostile tribesmen. Keeping his head, the Spartan commander calmed his panicking troops, who were themselves only freed helots and Spartan allies, not born-and-bred to war Spartiates like himself. He ordered them to form-up into a large hollow square. Placing his non-combatants into the interior of the square, he now marched them through the light-armed tribesmen surrounding them. Faced by heavy infantry in good order, these were loath to close with the redoubtable Peloponnesian hoplites.

Their armor and large shields protecting them from hostile missiles, Brasidas’ force succeeded in extricating themselves with little loss. This use of the tactical square in hostile country presaged the march of Xenophon’s 10,000 twenty-three some years later, and may have inspired Xenophon (guest-friend of the Spartans) and his tactics.

Their armor and large shields protecting them from hostile missiles, Brasidas’ force succeeded in extricating themselves with little loss. This use of the tactical square in hostile country presaged the march of Xenophon’s 10,000 twenty-three some years later, and may have inspired Xenophon (guest-friend of the Spartans) and his tactics.

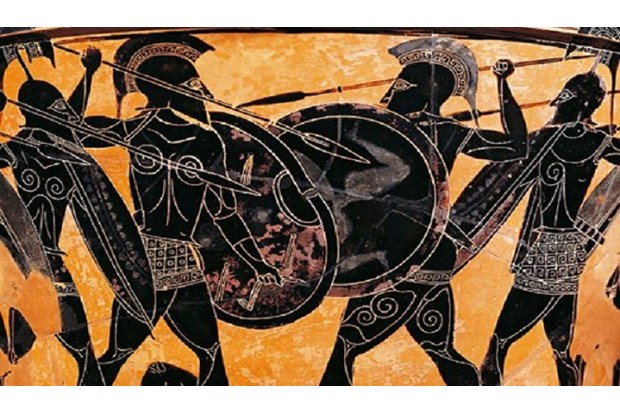

Heavy infantry hoplite from this era

In April of 422 the Athenian general (and political demagogue leader) Cleon the Tanner sailed for the north with a new army and the mandate to restore Athenian control. In particular, his goal was to recapture Amphipolis, with its nearby mines and wealth of ship-building timber.

Cleon enjoyed initial success, recapturing Torone and perhaps other towns. Moving on to Eion, Cleon established a base. Then, marching his army north to Amphipolis, he reconnoitered the city.

Brasidas watched the Athenians outside the walls. Though outnumbered, he hastily formulated a plan of attack. As Cleon’s forces began to withdraw back toward Eion, the southern gates opened and Brasidas, at the head of his forces, charged out!

Cleon’s hoplites wheeled left to engage the Peloponnesians, and a fierce fight developed. Meanwhile, a second Spartan force, dispatched by Brasidas from the city’s northern gate, now came at a run around the eastern walls, to attack the Athenian’s right flank. Here stood Cleon, on the extreme right, the place where all phalanx commanders took their station.

The right flank of a phalanx is its most vulnerable place; its shieldless side. Charged here by the Peloponnesians, the Athenians gave ground, and were soon in complete rout. Cleon himself was slain in the fighting.

Unfortunately for Sparta, Brasidas too was killed in the fighting, leading the initial frontal charge into the Athenian phalanx. He was buried at Amphipolis, and honored in the city as a second founder. In Sparta, he was remembered with great honor as a hero of the city. His neodamodeis veterans were allowed to remain together as a regiment upon their return to Sparta, and to call themselves the “Brasidans”.

Brasidas was perhaps the most intrepid, bold, and forward-thinking Spartan general of the war; with Lysander (who appears later in the war) his only rival for the title as the best general Sparta ever produced. His ability as a politician and diplomat, unusual in any military man (much less a Spartan), were exceptional and allowed him to win over the Chalcidice with little bloodshed. In battle he thought beyond the simple clash of phalanx, using ruses and flank attacks to good effect. As was the case with the WWII German general Erwin Rommel, he had that rare ability of inspiring admiration in the very enemies he was fighting. It has been argued that Thucydides’ (an Athenian general who opposed him) presentation of Brasidas is nothing less than a Homeric celebration of the epic hero’s valor. Like Achilles, he died too young.

Thucydides points out that both Brasidas and Cleon represented the most bellicose elements in their respective cities. With both these leaders removed, peace could be negotiated.

Exhausted, the Spartans and Athenians soon concluded the Peace of Nicias; bringing the first half of the Peloponnesian War to a close. At the signing ceremony, one of the seventeen “most esteemed” Spartans taking part was Tellis, father Brasidas; so-honored in memory of his son’s heroic services to his country.

Pingback: SPARTANS, ELITE WARRIORS OF ANCIENT GREECE 5: BRASIDAS’ MACEDONIAN CAMPAIGN | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page – Dave Loves History

Reblogged this on Ritaroberts's Blog.

Pingback: SPARTANS, ELITE WARRIORS OF ANCIENT GREECE 6: SPARTA’S REPUTATION IS REDEEMED AT MANTINEA! | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page