Unique among the territories of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, Britain succeeded in holding back and even reversing the tide of Germanic conquest for nearly two centuries. This was an age of heroes… It was the Age of Arthur!

This is the twentieth-part of our discussion of Britain in the 5th though the mid-6th Century A.D. It is a fascinating period, with the Classical civilization of Greece and Rome giving way to the Germanic “Dark Ages”; the sunset of Celtic-Roman culture in Britain.

(Read Part Nineteen here. Or start from the beginning, with Part One!)

______________________________________________

The Battle of Mons Badonicus (Badon Hill) was over. The greatest army the Anglo-Saxon powers had ever gathered together, with the intent of once-and-for-all putting paid to their Romano-Celtic enemies in the west; which had marched under the standards of at least three Saxon kings (the Bretwalda, Ælle of the South Saxons or Sussex, Oisc of Kent, and Cerdic of the West Saxons) and numerous chieftains and warlords across the south of Britain to Bath, and laid siege to that city; had been broken on the slopes of nearby Badon Hill by one fearsome charge of Arthur and his Combrogi. The ninth century chronicler, Nennius, tells us of Arthur’s charge:

“… in it nine hundred and sixty (Saxon) men fell in one day, from a single charge of Arthur’s, and no-one lay them low save he alone.”

We have no idea how many of the Saxon host survived the pursuit and slaughter that followed. But it is unlikely that many lived to return to their homes in the eastern part of the island or beyond the sea. An entire generation of Anglo-Saxon warriors was that day decimated, and 50 plus years of conquests reversed.

Arthur had won a great victory at Badon. At a time when everywhere Germanic warriors were carving-up the carcass of the Roman Empire and founding kingdoms within its former boundaries, in Britain the native resistance had succeeded in throwing back the invaders. Under first Ambrosius Aurelianus and then Arthur, the last glimmer of Roman civilization was kept alive, and the barbarian tide held at bay.

Yet the price had been high: the loss of nearly everything the victors had taken-up arms to defend. “Ambrosius and Arthur had fought to restore the Roman civilization into which they had been born. But in most of Britain, the society of their fathers was ruined beyond repair.”[1]

The rich lowlands of the south and east, always the most Romanized areas of the former province, were devasted. The Roman cities and country villas that had dotted the landscape were long sacked and lay in ruins. The Romano-Celtic residents that, since the organization of Britannia following the Claudian invasion of the island in the 1st century, had farmed, traded, or otherwise conducted business here were long dead, immigrated west or beyond the sea, or enslaved by the Anglo-Saxon conquerors.

Restoring the Roman province of Britain as a single entity was now the task left to Arthur and his victorious Combrogi [2].

How successful was Arthur in this endeavor?

We don’t know. The details of this period have been lost to history. But that Arthur left the island in a far better state than it was prior to his birth, and likely better than it had been since at least the late 3rd century under Roman rule; is attested to indirectly by the chronicler, Gildas. Who, growing-up during that age and writing some decades after, and who is our lone near-contemporary source, looked back upon the age of Arthur’s reign with nostalgia. As a time of stable government, when “rulers, public persons and private, bishops and clergy, each kept their proper station“; when the “restraints of truth and justice” were still observed. It was a time of well-ordered government and society, a renaissance perhaps of Roman civilization made possible under the strong leadership of Arthur.

It lasted as long as Arthur and those who fought in the Saxon wars still lived, about a generation. It was followed by a slow disintegration of national unity and fragmentation back into petty kingdoms. The lands of “Logres“, the low lands of central and southern Britain long occupied or threatened by the Anglo-Saxon invaders, freed by Arthur’s victories and rebuilt as the center of his realm, once again reverted to the rule of the Anglo-Saxons in the decades after his death.

But for some twenty years following Badon, Britain enjoyed a kind of golden age, which in time spawned the many legends of Arthur and “Camelot”.

RECLAMING LOGRES

How Arthur took possession of and ordered his realm following his final great victory over the invaders is of course unknown. But we can speculate intelligently, and as throughout this series, attempt to build a narrative that both follows the facts (few as those may be) and explains as best we can the unknowable. In essence, to create a working, sensible hypothesis.

Let us start by looking at the island in the early years of the sixth century, immediately following the destruction of the Saxon forces at Badon.[3]

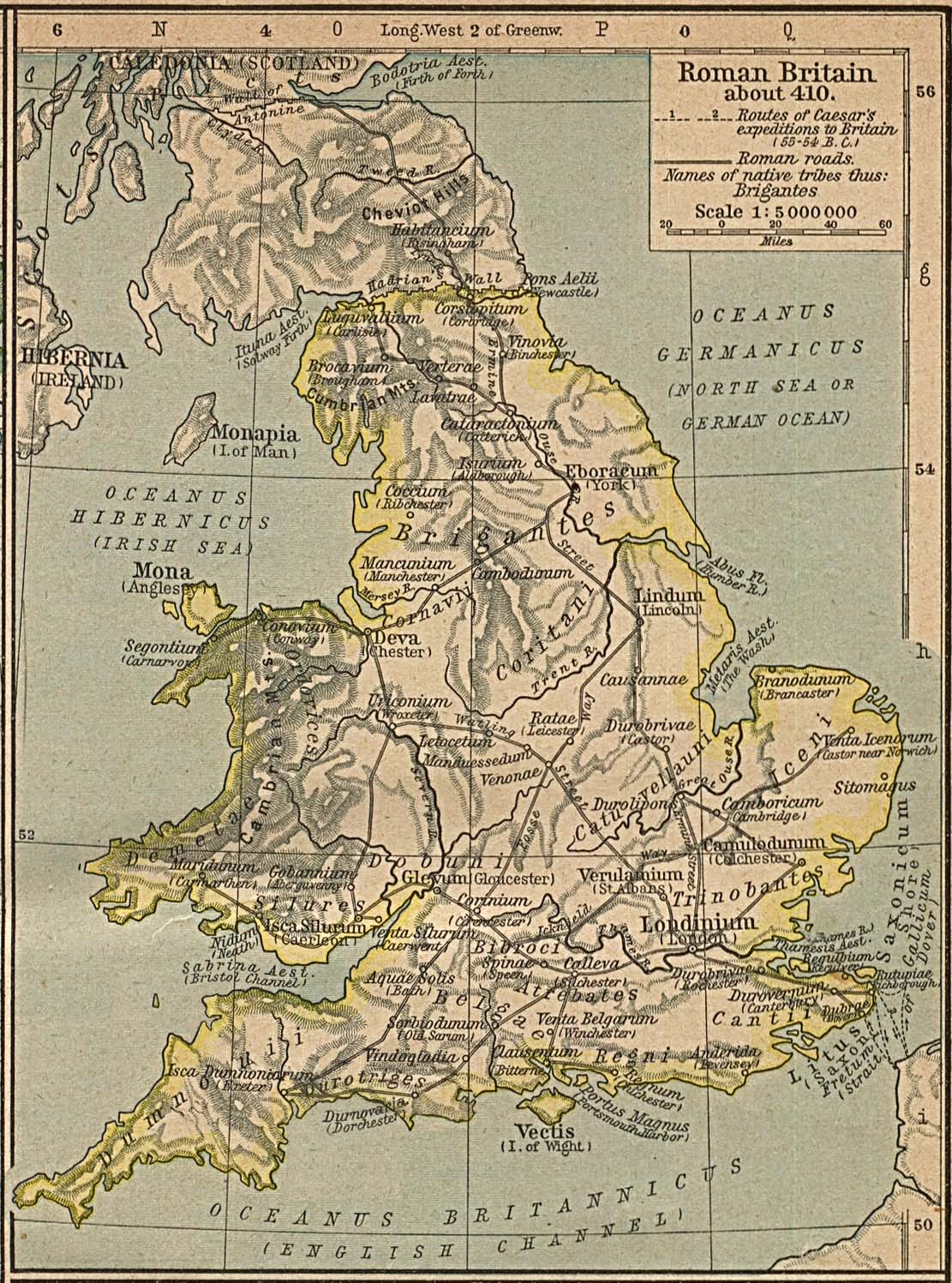

Before Badon the island had been roughly divided into three parts: the western portion, divided into Celtic tribal kingdoms; the eastern region, ruled by Anglo-Saxon warlords and kings; and the debatable lands between the two. This latter region stretched from the midlands in the north (likely through the Pennines) down to the marshes of Hampshire in the south. Mostly depopulated by the previous generation of desultory warfare between the two races, it was dotted with encroaching Anglo-Saxon settlements and the occassional British hillfort, still holding out as islands of resistance.

As leader of the Romano-Celtic resistance, Arthur had spent years beating-back the ever-creeping Germanic settlement of the debatable lands, and engaged in the occassional raid into Saxon lands. The unexpected, almost miraculous victory at Badon left the Saxon kingdoms of southern Britain bereft of defenders. The scale of the defeat stripped the Germanic settlements of every able-bodies male of military age, as well as the Saxon leadership. Kings, thegns, and humble carls had all marched off to what was supposed to be the final despoiling of the west. Their deaths (or capture, which is tantamount to the same thing in this circumstance) left a temporary vacuum; an opportunity that would never come again to role back the invasion and restore Logres.

In the hours and days immediately after the battle, Arthur’s horsemen would have pursued the fugitives relentlessly. Most would have found no shelter within which to reorder, and been harried and cut down relentlessly. Exhausted men on foot, fleeing a battle, are especially vulnerable to pursuit and slaughter by horsemen. Likely most of the Saxon army perished or were captured in these sanguine hours. Only Cerdic, whose stronghold was relatively near at hand within the southern Hampshire marshes, could have gotten clear with the survivors of his warband intact.[4] The men of Sussex and Kent had no such easy refuge, and most would have perished.

Returning to Bath, Arthur would have needed some time after Badon to rest his forces and organize the next step. It would take careful planning, followed by bold, audacious action.

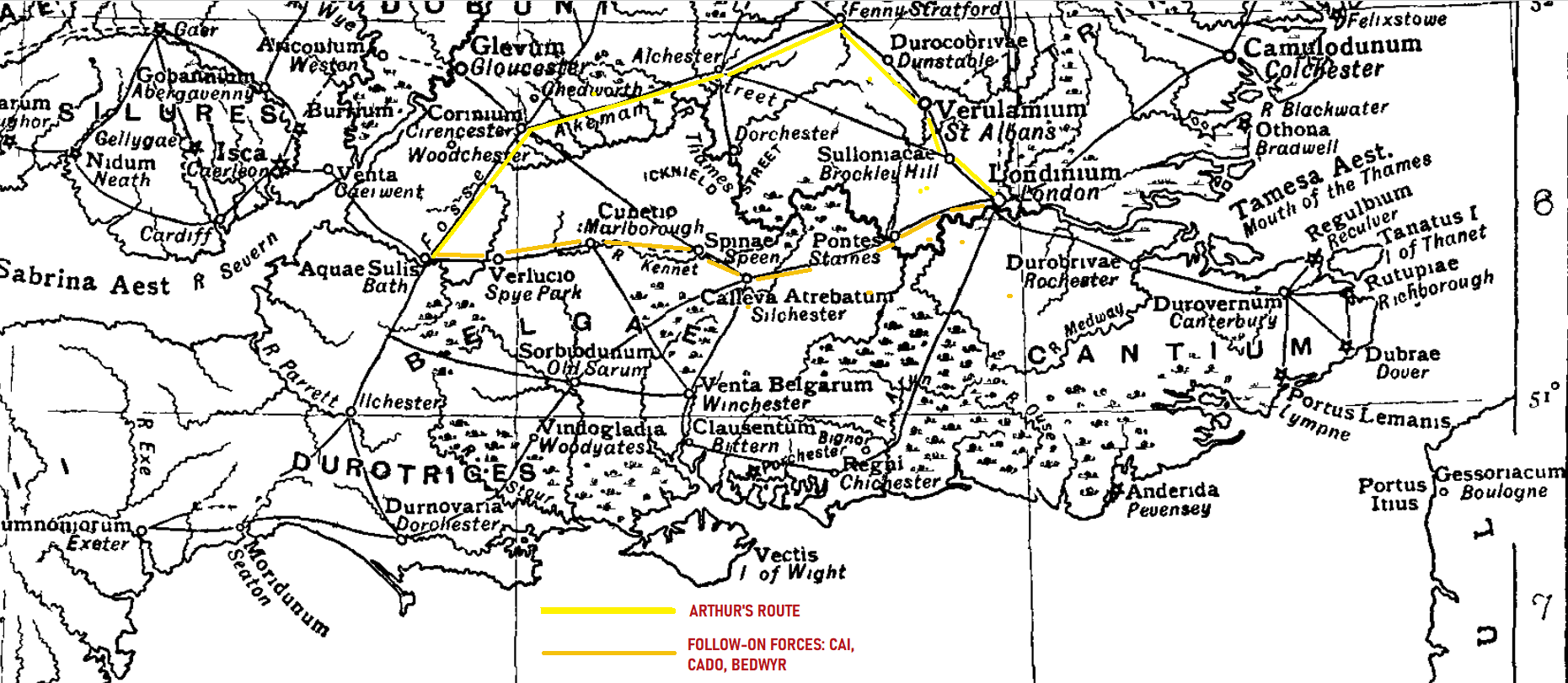

Dividing his forces into several columns for ease of supply and rapidity of movement, Arthur would have advanced eastward, north and south of the Thames. His main thrust, aimed at distant Londinium, the former Roman capital of the province, would under other circumstances have followed the same road likely used by Ælle’s army in their march west: the so-called Devil’s Highway. This unnamed Roman road, an extension of the Port Way from Bath to Silchester, was the main east-west route south of the Thames for centuries before and centuries after Arthur.

But the passage of Ælle’s forces in the previous weeks would have stripped the area bare of what little supplies may have been available. (As much of the region between Bath and Silchester was “debatable lands” disputed by both parties for a generation, human habitation was already scarce before Aelle’s invasion.) We can only speculate, again; but a military leader of Arthur’s abilities would have eschewed this route in favor of one both less obvious and which a flying column of horsemen could find fodder and forage. Since it was important to keep a sword in the Saxon’s back and prevent them reorganizing, Arthur likely sent a detachment of horsemen that way to scatter any pockets of gathering resistance.

Arthur may also have tasked one of his officers, perhaps Cei or Bedwyr, or even Cador of Dumnonia, to gather supplies and follow-on with a larger force of horse and foot, with attendant supply wagons; to advance methodically down this road, “policing up” prisoners, destroying Saxon settlements (abandoned or still occupied), and to meet him at Londinium. Such a force was a logical precaution, both to secure the area south of the Thames and to make sure that Cerdic had indeed skulked off to return to his marshes, and would be no immediate threat.

Arthur, with the bulk of the Combrogi and extra supplies on baggage horses, would lead the flying column north of the Thames. His route would take him first back north, up the Fosse Way and through the Costwolds to Corinium Dobunnorum (Cirencester). From there, his band would transfer to Akeman Street, the east-west road north of the Thamesm, which connected the Fosse Way to Watling Street at Verulamium (St. Albans). At Verulamium Arthur would turn again, galloping for Londinium.

Once the capital of the Roman province of Britannia, boasting some 60,000 residents, Londinium was a city in decay if not ruin. Spared the initial sack and slaughter that had befell many smaller towns in the days following the great Saxon mutiny against Vortigern in the 450s (the “Saxon Terror“, see Part Five), if Londinium was indeed still a functioning city (and it is uncertain that it was still inhabited by 500 AD) it was likely maintained as a tributary city of the surrounding Saxon kings. Perhaps for purposes of trade an open city, where traders from across the Channel and North Sea were free to bring their highly prized goods. But the economy of the island and its trade with the mainland had been badly impacted by the chaos and wars of the last half-century. Trade required peace and order, both long absent in Britain as well as the rest of the former Western Empire. Once thriving Londinium was now an island precariously surrounded by Anglo-Saxon settlement.

Did it open its gates to Arthur’s victorious horsemen? Again, if still inhabited and functioning, almost certainly. Word of the disaster inflicted upon the Saxon forces in the west would have undoubtedly preceded Arthur’s sudden arrival. On the other hand, he may have found a largely abandoned ruin, with few if any inhabitants still living within its crumbling walls. Whatever the case, when the rest of the British forces arrived in the weeks following, they would have likely been put to work strengthening the fortifications and making the place once again habitable.

At some time following Badon, Arthur likely sent out emissaries to his beaten foes. Riders bearing signs of peace (perhaps birch branches) rode into the now weakly-held strongholds of Jutes of Kent, the South Saxons of Sussex, and the Anglish of Norfolk. Inviting them to a great peace conference, the first between the British and the Germanic invaders in a generation.

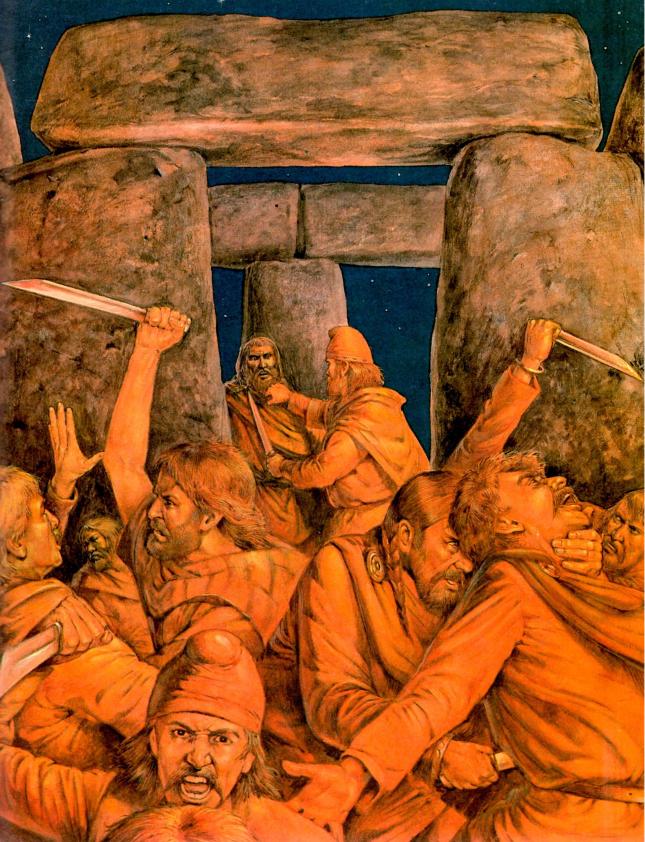

The last such peace conference has ended in blood and murder.[5] The “night of the long knives”, where the leadership of Roman Britain was murdered. Vortigern and Hengist had agreed to make peace. At the celebratory feast each Saxon thegn was seated beside a Briton officer and official. As the evening drew on, with many toasts to renewed friendship and peace, the Saxons were careful to imbibe but sparingly.

At some point, Hengist raised his drinking cup in a final toast. This was the signal: as the British officers drank deep to peace, the Saxons pulled out their daggers and fell upon the Britons beside them, slaughtering all. Only Vortigern himself was spared. The leadership of the Romano-British state was decapitated, and the southeast of Britain subsequently ceded to the Saxons by Vortigern in return for his release.

These events, 50 some years before, must have been in the back of the minds of all who attended Arthur’s conference. But the atmosphere now was very different. Arthur was no fool like Vortigern, and the now beaten Saxons had no wily Hengist to lead them.

Where the great peace conference following Badon occurred; who attended; and for how long it lasted is unknown. Londinium, after he took possession, is as good a place as any in Britain: close to the enemy’s enclaves, and symbolically the heart of the island. Attendees likely included the Celtic kings of the west and north as far as Strathclyde (or their representatives); and the new leaders of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Among these was Arthur’s friend, Cado of Dumnonia; and the grandson of Hengist, Octa of Kent. The Anglian kingdom of East Anglia had not yet coalesced under the Wuffingas, but whatever warlord ruled the North Folk likely came to Arthur’s conference as well.

In the end, Arthur imposed upon them all his authority, and redrew the borders of Britain.

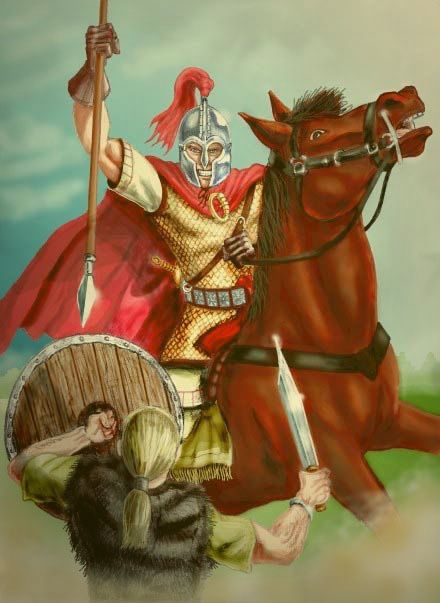

Arthur receives the homage of Briton, Pict, and Saxon leader, hailed as Emperor

The island was to be partitioned. This would not have set well with some, but it was a practical solution that would end a generational war to the knives between Celt and German, and reestablish a working state throughout Britain, as hadn’t been seen since Vortigern. There is no direct evidence for this. But Gildas indirectly refers to the resulting division of the island, writing a generation later of the lamentable lugubri divortio barbarorum, the “melancholy partition with the barbarians”; which prevented the British from visiting some of the shrines of Christian martyrs, now in Anglo-Saxon territories. In Gildas words can be detected the first hint of disaffection among the Christian Britons with Arthur’s policies; which would grow in the western highlands as Arthur’s reign drew on and he was less-and-less seen as their champion against the heathen, and more the distant lowland overlord, his hand heavy on their affairs.

It is likely that the defeated Germans were allowed to remain in Kent, Sussex, and Norfolk. Archeological evidence points to their continued presence in the far eastern portion of the island during this period, even as it retreated in the former “debatable lands”. These Anglo-Saxon petty kingdoms were roughly analogous to the old Roman military district known as the Saxon Shore. This was the district facing the North Sea and eastern Channel coast, where “Saxon” raiders in Roman times were most likely to make landfall. In early chapters we have postulated that the chain of Roman forts along the coast here were themselves garrisoned by Anglo-Saxon foederati. It was common late Roman practice to set “barbarians” on the boarders of the empire to check the advances of other barbarians. But Arthur’s settlement didn’t return the Anglo-Saxons to foederati. They would be allowed to stay in Britain (the only home most of them had ever known) as Laeti; communities of barbari granted land in imperial territory on condition they live peacefully with their Roman neighbors, and provide recruits for the Roman army.

CAMELOT

Thus, the Anglo-Saxon kings would be vassals of the British ameraudur [6]. As would the Celtic petty-kings of the west and north, whom Arthur had led in war for a decade. For as Arthur and his companions established peace on the island, and set about restoring the order they remembered from the past, the only model they would have had was the Roman imperial system. With imperial rectors appointed by Arthur running the civil administration of the provinces, supported by prefects and procurators. With military districts run by duces (Cado for one, petty-king of Dumnonia, becomes one of Arthur’s duces under the new imperial structure), and mobile forces commanded by comites. And over them all, an emperor, in Welsh “ameraudur”. The obvious title for Arthur, former dux bellorum of the British resistance, now victorious conqueror at the head of a loyal army, was emperor.

How well this new arrangement and return to civil authority, however imposed by military force, sat with the quarrelsome Celtic lords of the west country and highlands of Cumbria and the north can only be guessed at. But we can imagine that many took umbrage at becoming the vassal of their erstwhile general. Particularly as their usurped powers, taken on in the absence of Roman civil government, were during Arthur’s reign curtailed and returned to civil authority.

Most of the Welsh poems and ecclesiastical traditions, and later Medieval legends of Arthur, come out of this period, the 20 some years of his reign. Many of these highland sources portray him not as their beloved war leader in the national effort to throw back the barbarian. Instead, he is often portrayed as lowland tyrant, cruel and even lascivious and at odds with church authorities and saints. When not hated or feared he is seen as a remote overlord, the all-powerful lowland overlord surrounded by soldiers, sometimes helpful and other times at odds with the local highland princes and heroes. His authority extends across the island, into Cornwall and Wales and even beyond the Clyde and Forth.

It is from this period, when Arthur was overlord of Britain that the legends penned in later centuries drew from and referred to. Including his supposed seat of power, where he held court: Camelot.

A realm like Arthur’s, cobbled together out of the debris and destruction of long war, could perforce have no one place where the ruler sat in judgement. Arthur no doubt spent much of his reign in the saddle, visiting the various petty realms that comprised his “empire”; and where he sat he held court. The Norman romances, drawing on earlier native sources, name some of these: London, Luguvalium (Carlisle in Cumbria), Caerleon in south Wales (in Roman times Isca Augusta or Isca Silurum).

But one, Camelot (sometimes in Medieval sources spelled Camalot) was his most frequent residence. As noted above, an incipient realm such as Arthur’s, rising as it did out of conquered lands and from the ashes of the former Roman province, was not one that could be ruled from one place. But Camelot was as close to a capital as he could enjoy.

There is no such place, spelled that way, anywhere in Britain. But a likely location whose name closely resembles this is Camulodunum (Colchester). The “Stronghold of Camulos” (a Celtic war god the Romans identified with Mars), was well-located as an advance base to keep an eye on the Anglo-Saxon settlements and (now) subject kingdoms of the Saxon Shore. From here he could maintain the new borders between Logres and the barbarian lands along the coast.

But a restored Romano-British kingdom of Britain was one that would not last. As Ireland would find throughout its long history; as Gaul had found in the time of Caesar; the Celts are more happy divided than united, fighting each other as readily as any invader. Celtic Britain was no exception, and like Brian Boru 500 years later, the unity Arthur imposed would not long outlive him.

NEXT: THE ROAD TO CAMLANN

———————————————-

Notes:

- Morris, John (1973), The Age of Arthur, Ch 6, p 114.

- Welsh: meaning companions, countrymen, or comrades-in-arms. In this context it refers to Arthur’s household cavalry, similar to the bucellarii of late Roman generals.

- Like so much else regarding Arthur, the date of Badon is disputed. I have chosen to follow the Annales Cambriae date of 516 AD, although 493 and 501 are equally plausible.

- For Cerdic’s role in the Badon campaign, see Part Nineteen.

- See Part Five.

- Emperor

Pingback: THE AGE OF ARTHUR, PART TWENTY: EMPEROR ARTHUR – Glyn Hnutu-healh: History, Alchemy, and Me

Reblogged this on Ritaroberts's Blog.

Thanks again for the link. I have re connected.

Glad to see this series resume, and equally happy to know you will finish out this historical Analysis of Arthurs story to its proper conclusion ;o)