The 30 Years War had raged for ten years, and for the Protestant cause it had been a string of disasters. Then a new champion took-up the sword to defend the faith against the Catholic armies of the Empire: Gustavus Adolphus, the “Lion of the North”! In his first battle against the ever-victorious army of Catholic League General Tilly, the Swedish king would prove his name and cement his renown as one of history’s “Great Captains” of war.

In 1628, the Hapsburg dream of a united Catholic Germany, ruled from Vienna, seemed nearly realized. Ten years into what would become known as the Thirty Years War, Catholic-Imperialist forces had crushed all opposition from Bohemia to Denmark. The Protestant Electors of the Rhine principalities had been humbled, the Czechs brought back into the Catholic fold, and the Danes defeated and humiliated. By 1630, the Imperial armies of Tilly and Wallenstein were camped along the Baltic shores, with Germany seemingly pacified behind them.

Only Protestant Sweden, across the icy waters, remained defiant.

When King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden crossed the Baltic and landed in Germany with a mere 13,000 men, the Hapsburg Emperor Ferdinand II sneered, “So, we have another little enemy!”

However, the “Lion of the North” was an enemy of no little ability.

Scion of the warrior Vasa dynasty, Gustav II Adolf was the most brilliant offshoot of a family tree known to produce soldiers and statesmen of exception. Coming to the throne in 1611 at the age of 16, he inherited three wars from his father: against Denmark (the Kalmar War), Russia, and against Poland. The first was concluded by treaty in 1613; and the second ended in 1617 with the Treaty of Stolbovo, which excluded Russia from the Baltic Sea. The Polish war dragged on till 1629, ending with the Truce of Altmark, which transferred the large province Livonia to Sweden.

Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden

Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden

These conflicts early in his life not only greatly enhanced the territory and power of the Swedish Empire, which now controlled the eastern Baltic; but honed Gustavus’ native abilities as a commander. In Poland he faced a very good commander in his own right, the great Hetman of the Polish Commonwealth, Stanislaw Koniecpolski. Much of the talent he showed later for rapid and unexpected maneuver may have been learned fighting against this Polish hero, whose operational hallmark this was. Gustavus also no doubt used the Polish war to develop his tactical theories and to train his small, professional Army into a finely tuned machine.

In June of 1630 Gustavus landed in Pomerania, where Sweden already had a base at Stralsund. The Swedish expeditionary force was financed, in large part, by French money: the far-sighted Cardinal Richelieu preferring a continuation of the religious war in Germany to a united Hapsburg Germany on France’s doorstep. Gustavus was also aided by the Emperor’s dismissal of Wallenstein earlier that year, after that great Imperial commander’s failure to capture Stralsund. While the bulk of Wallenstein’s army joined Tilly’s, many thousands of veteran mercenaries abandoned Imperial service in disgust, and instead joined the Swedish king.

Gustavus set about methodically taking one north-German fortress and town after another. Many surrendered upon a mere show of force, as the northern Germans, largely Protestants, were inclined to support any Protestant champion.

Even so, at the start of the following year the Swedes were still too weak to offer battle against Tilly’s superior army. Negotiations for a strengthening alliance with the Protestant states of central Germany seemed to be going nowhere, as the timid princes were unwilling to brave the wrath of Tilly’s Imperial army. Then Protestant Magdeburg was captured and sacked by Tilly’s army on the 20th of May 1631, in an act of barbarity so savage it shocked the sensibilities of Catholic and Protestant alike. Of the 30,000 citizens, only 5,000 survived the orgy of rapine and murder by the Imperial army. For the subsequent fourteen days, burned and mangled bodies were carried down the Elbe River, which became choked with the dead. The Imperial cavalry commander, the Graf zu Pappenheim, wrote:

It is certain that no more terrible work and divine punishment has been seen since the destruction of Jerusalem. All of our soldiers became rich. God was with us.

When Tilly moved into Saxony, pillaging far and wide to feed his ravaging host the Elector was finally moved to throw his lot in with the Swedes. Gustavas marched on Leipzig, which Tilly’s army had just captured along with enormous booty. His 23,000 Swedes were now reinforced with 18,000 Saxon troops, creating a united force of some 41,000.

The Swedish lion now offered Tilly battle a few miles northwest of Leipzig, on the plain of Breitenfeld.

Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly

Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly

FORCES ENGAGED

Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, the seventy-two-year-old Walloon general commanding the Imperial army, had learned his trade in the Low Countries under the famed Duke of Parma. He was an accomplished commander, and had defeated every enemy who’d dared face him in battle. Though outnumbered in the coming battle, experience had shown that his 35,000 professionals were the equal of any number the Protestants could raise against them.

As veteran as their commander, Tilly’s Imperial army had campaigned for 10 years from the Bohemian Alps to the Baltic. Trained in the Spanish model, the heart of this force was the Imperial tercios: massed blocks of pike-and-musket armed troops. Like moving fortresses these ponderous squares varied between 3,000 and 1,500 men each, drawn-up in up to 30 ranks. Tilly had seventeen tercios deployed at Breitenfeld, in all about 25,000 trained and experienced infantry. By reputation these were the best foot in the world.

(Above) Imperial/Spanish tercio, detail from contemporary illustration. (Below) Breakdown of pike vs “shot”

By contrast, Gustavus’ reforms of the Swedish infantry had created a much different tactical force. Disdaining the ponderous tactics of the tercio, and building upon the work of Maurice of Nassau, Gustavus’ foot were organized into smaller, more flexible regiments and Brigades, the latter of 1,500 men. Unlike the Imperial tercio, the Swedes deployed in only 4-5 ranks deep; each brigade formed in a cross-shaped formation of pike and supporting musketeers. In battle, these brigades formed-up in two lines, with the brigades of the second line supporting the gaps between each brigade in the first. The Swedish system allowed the units to maneuver more rapidly on the field, without crowding each other, and to deliver a much higher rate of fire against the enemy.

In numbers and quality of infantry the Imperial forces had the advantage, particularly in quality. Tilly deployed about 25,000 veteran infantry to the Gustavus’ 15,000 Swedish veterans. Though Gustavus’ Swedish Brigades were trained to high level of excellence, the 9,000 Saxon allied infantry were poor quality militia, armed and trained in outdated pike tactics and with few muskets. Tilly had little to fear from these.

17th century pikeman, set to receive a charge

In the 17th century infantry were the solid core of an army, with the great blocks of pike-and-shot lumbered across the battlefield like human fortresses. But cavalry were the decisive arm in battle, maneuvering on the flanks and in the gaps: the hammer to the tercio’s anvil. Cavalry were a large and effective part of both armies at Breitenfeld.

17th century musketeer

17th century musketeer

There were of three types of horse during this age in Western Europe: cuirassiers, harquebusiers, and light horse.

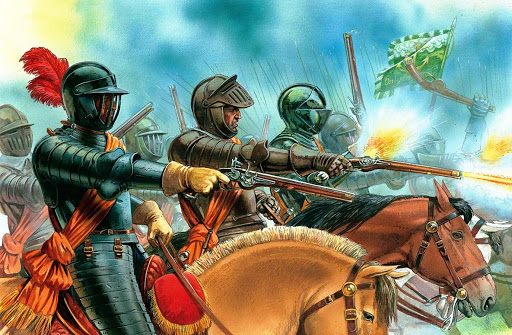

The first of these, the cuirassiers, were the supreme heavy cavalry of the day. These were horsemen equipped in three-quarter plate armor (including a cuirass that was proof against firearms) and armed with sword and pistol. They were trained to charge the enemy, the first two ranks discharging their pistols at close quarters before drawing their swords and galloping into the enemy’s ranks. Sweden, poor in resources and lacking large horses, fielded only one regiment of these in the war. The Imperials, on the other hand, had the services of many thousands of such cuirassiers, commanded by Pappenheim, who due to the color of their armor were sometimes referred to as the “Black Cuirassiers”.

The second type, the harquebusiers, were a hybrid “medium cavalry”, the archetype for the dragoons of the following century. Though equipped and trained with a harquebus to skirmish with the enemy, mounted or dismounted, they were also quite capable of charging with sword, and many regiments equipped their troopers with a cuirass and helmet.

Finally, there were the light cavalry. The Imperial army had a number of Croat and Hungarian light horse. These were skilled scouts and foragers (the Croats in particular earning a fearsome reputation as plunderers), and in battle could harass the enemy’s flanks or ruthlessly pursue a broken foe. Their counterpart in the Swedish forces was provided by Finns, commanded by the capable Gustav Horn. These were excellent scouts and foragers, and even more feared in battle than the Croats. These were known as Hakkapeliitta, there name based on their battle cry: hakkaa päälle (“Cut them down!”).

Swedish cavalry

In pure numbers Tilly’s Imperial cavalry were outnumbered by their Protestant opponents: 9,000 to Gustavus’ 13,000. But the allied cavalry were more lightly equipped, and none were as heavily armed (and armored) as Pappenheim’s feared Black Cuirassiers. Worse for the Swedish king, 5,000 of Gustavus horsemen were Protestant German contingents of doubtful quality.

In Poland, a land of superb cavalry, Gustavus had resorted to the Huguenot practice (from the French Wars of Religion in the previous century), of detailing small units of musketeers to support the cavalry with fire. These “commanded shot” gave the otherwise over-matched Swedish horse a fighting chance at breaking the charge of better mounted and equipped Polish cavalry, particularly the famed “Winged Hussars”. This practice continued in Gustavus’ German campaigns, and would play a key part in the coming battle.

Only in number and quality of guns was the Imperial army at a disadvantage. Tilly’s were larger but less mobile than those of the Swedes. Once placed these overly-heavy guns were difficult to move, and so usually stayed in one place throughout the battle. The Swedes and their Saxon allies had as many heavy guns, but Gustavus, a great proponent of artillery, had reformed that arm; standardizing the calibers in use and lightening the guns themselves. The Swedish guns were thus easier to maneuver and faster to load. Additionally, each of the Swedish Brigades had their own integral light artillery, in the form of six light 3 pounder “regimental guns” per Brigade. These were easy to manhandle in battle, and could sustain a relatively rapid rate of fire. Finally, Gustavus had cross-trained his cavalry and infantry as gunners so that in a pinch they could man guns whose crews were slain, or turn captured enemy guns against their previous owners.

THE ARMIES DEPLOY

The morning of September 17, 1631 dawned bright and hot. Tilly drew up his 35,000 strong Imperial army along some two miles of frontage. He deployed these in two lines, with a small cavalry reserve. In the Spanish custom, he posted the bulk of his cavalry on both wings, covering the flanks of his stolid tercios in the center. The heavy Imperial guns were spread evenly across the front. A gentle slope favored his dispositions, and the day would begin with the sun at his back and in the eyes of his Protestant foes.

The Imperial forces were resplendent in the imperial colors of red and yellow, in what passed for uniforms, beneath buff coats and steel cuirasses.

The Imperial left was commanded by the renown Pappenheim, at the head of seven full cuirassier regiments. On the opposite flank, facing the Saxons, the Count Egon von Fürstenberg commanded another five cuirassier regiments, supported by a regiment of dragoons and one of Croat light horse. Fürstenberg also had a large number of heavy guns supporting his wing, destined to play a critical part in the struggle.

By contrast, Gustavus allied army must have presented a much meaner appearance than their Imperial foes. After months of sleeping in plowed fields, the Swedes in tattered blue and brown homespun presented a rustic site compared to splendidly-accoutered Imperialists across the field.

Swedish musketeers and pikemen in a life-sized diorama at Swedish Armeemuseum, Stockholm

Swedish musketeers and pikemen in a life-sized diorama at Swedish Armeemuseum, Stockholm

Gustavus drew up the seven brigades of Swedish foot in two lines, backed by a reserve of Finnish horse. His Saxon allies he placed on his left. The Swedish Brigades were deployed a chessboard fashion, the three brigades of the second line covering gaps equal to their frontage between the four brigades of the first line. Across their front were twelve heavy guns in one grand battery (this aside from the 42 light regimental guns integral to the infantry Brigades). The “grand battery” was commanded by young Lennart Torstensson, a gifted artillery prodigy who, one day, would prove his own worth as an army commander. The infantry of the center were commanded by Maximilian Teuffel, a German soldier in Swedish service.

On the Swedish right were 4,100 horse supported by 1,200 “commanded” musketeers, the wing commanded by the veteran Johan Banér. The Swedish left comprised 2,300 cavalry supported by 800 musketeers and commanded by Gustavus’ second-in-command, Horn.

Beyond Horn’s cavalry wing and facing Fürstenberg was the Saxon army, under the nominal command of their Elector, John George, assisted by a professional German soldier-of-fortune, Hans Georg von Arnim. The Saxons deployed their blocks of pikemen into a wedge formation, supported on either wing by massive wedges of cavalry. Such a formation can only be of use in the offense, and it is evident that Gustavus, who planned to let the Imperial army break itself against the superior Swedish firepower, was not on the same page as his ally. As events would show, this would prove very nearly disastrous for the Protestant allies in the battle soon to unfold.

THE BATTLE OF BREITENFIELD

The battle began with the Imperial screen of Croat light horse attempting to interfere with the Swedish deployment. They were thwarted when Banner unleashed the shaggy Finnish Hakkapeliitta upon them. The Finns gave the Croats the kind of savaging they were used to dealing out, and the Croats scattered back to their own lines. No doubt satisfied with themselves, the Finns fell back through the gaps in the Brigades and rejoined the reserve.

The battle then settled down into an artillery duel, over the next two hours, each side attempting to silence the other’s guns. The Swedes’ better trained crews fired three-to-five times faster than their opponents and soon got the upper-hand. In response, Tilly ordered his cavalry on both wing to attack. [1]

On the Imperial left the fiery Pappenheim led some 5,000 of his Black Cuirassiers in a furious charge on the Swedish right-wing horse under Banér. Expecting to crush the lighter Swedish horse (even whose “heavy” regiments had little more than a simple cuirass worn over a buff coat), Pappenheim’s squadrons received an unexpectedly stout reception: disciplined volleys by the Swedish “commanded” musketeers supporting the Swedish horse. These salvos was followed-up by short, sharp charges by Banér’s squadrons. This “one-two” punch through Pappenheim’s riders back on their haunches. Attempts to swing wide and outflank the Swedish line were met by squadrons and companies of the second Swedish line, who, drilled to meet just such a move, coolly wheeling out to meet and greet the Imperialists in similar fashion.

Seven times that afternoon Pappenheim, the scarred veteran of countless charges, reordered his squadrons and flung them once again against the ill-mounted, contemptible Swedish horse and the impudent musketeers operating between their squadrons. Each time these latter darted out, deployed, and discharged a deadly hail of lead into his massed squadrons. Into the resulting confusion, the Swedish horsemen again-and-again counter-charged, then falling back in disciplined fashion to reform. Pappenheim’s dwindling regiments recoiled each time frustrated and bloodied.

Imperial cuirassiers, discharging pistols into the faces of their enemies

Imperial cuirassiers, discharging pistols into the faces of their enemies

Meanwhile, on the Imperial right, Fürstenberg’s cuirassiers enjoyed a very different outcome against Gustavus’ Saxon allies. Supported by heavy cannonade the Imperial cavalry charged the inexperienced and poorly led Saxons that formed the left of the allied line. Deployed for attack and not defense, the Saxons were ill-prepared to receive this assault, which proved too much for the ill-trained militiamen.Despite their officers best efforts to steady them, they dropped their weapons and fled the field in utter rout! With the blades and pistols of Fürstenberg’s riders in their backs, the 18,000 strong Saxon army quitted the field in mass.

At a stroke, Gustavus was deprived of forty-five percent of his army, and his left-wing laid bare. The veteran Tilly saw his opportunity, and now ordered his infantry to advance to their right at the oblique, in an effort to take advantage of the situation and outflank the Swedes.

Fortunately for the Protestant cause, Fürstenberg needed time to reorder his squadrons; while the infantry of the Imperial center also took time to respond: like an elephant the tercio had great mass but little spring. As they ponderously advanced into the void left by the Saxon rout, Gustavus’ intrepid second-in-command, Gustav Horn, had the time needed to order a response.

Coolly and quickly Horn ordered the Swedish second line of foot and horse (which included General John Hepburn’s crack Green Brigade of doughty Scotsmen) at right angle to their main line, facing and covering the exposed left. As Tilly’s infantry came around the flank into the ground deserted by the now routed Saxons, and began to wheel to their left, they were brought under fire by regimental light guns and some of the heavy guns of Torstennson’s main battery. Worse for Tilly, their redeployment was further slowed when Horn counter-attacked Fürstenberg’s horsemen, who’d attempted an ineffectual spoiler attack against Horn’s redeploying reserves but were instead thrown back into their own advancing tercios, causing disorder and delay.

At 6 pm the battle reached its climax on the Swedish right. Following the repulse of Pappenheim’s seventh assault, Gustavus took personal command of the squadrons on his right. Aware of the rout of the Saxons and the crises on his other flank, it was time to put-paid to Pappenheim and free his right from interference. Putting himself at the head of the savage Finnish Hakkapeliitta of his reserve, he led a counter-attack in mass against Pappenheim’s recoiling Imperials before they could reform. Repulse turned to rout, and the famed Black Cuirassiers were stampeded from the field, a portion of Banér’s squadrons in close pursuit. They did not stop running till they reached Halle, fifteen miles to the northwest.

The oblique advance of Tilly’s infantry to their right had left the Imperialist artillery batteries, which were stationary and unable to maneuver with the infantry, all but deserted where their front line had once been. With both his Hakkapeliitta and the remaining squadrons from Banér right-wing in hand, Gustavus swept across his own front to overrun Tilly’s guns, scattering the small body of Imperial reserve cavalry that attempted to interfere. Simultaneously, the unoccupied infantry of the Swedish center began wheeling forward to their left, as the whole battle shifted 90 degrees.

The cross-training of every Swedish soldier as gunner now paid dividends, as the Swedish horsemen dismounted and turned Tilly’s guns against the left flank of the tercios. Here they delivered a withering enfilade fire against their erstwhile owners. Torstennson’s main battery, no longer occupied with counter-battery fire against the Imperialist guns,wheeled 90 degrees and joined in smashing the tightly packed ranks of the Imperial infantry.

The cross-training of every Swedish soldier as gunner now paid dividends, as the Swedish horsemen dismounted and turned Tilly’s guns against the left flank of the tercios. Here they delivered a withering enfilade fire against their erstwhile owners. Torstennson’s main battery, no longer occupied with counter-battery fire against the Imperialist guns,wheeled 90 degrees and joined in smashing the tightly packed ranks of the Imperial infantry.

Even the best of soldiers can only endure so much. As casualties mounted, the ever-shrinking ranks of the Imperialist soldiers began to look to their rear. At that moment, Gustavus delivered the coup-de-grace, attacking simultaneously with cavalry and foot from his right wing and center; just as Horn led a charge of his left-wing cavalry around the right flank of the tercios. Facing envelopment, and the threat of having all retreat cut off, the Imperial army broke.

The Swedish cavalry were not inclined to mercy, and in close pursuit rode down the fleeing masses, inflicting with cold steel “Magdeburg quarter”. Only growing darkness and the presence of a deep wood to the rear of the battle put an end to the pursuit and gave the surviving Imperialist soldiers a place of succor.

Tilly, thrice wounded during the fighting and unconscious, was carried from the field by a small escort.

The battlefield was a charnel house, with perhaps as many as 12,000 Imperial dead or dying on the field. 7,000 had grounded arms and surrendered, most of which (being mercenaries) took service with the victor. Of the allied Swedish-Saxon army, some 5,000 were casualties, the majority of which were Saxon (by some accounts, the Swedes loss a mere 200 men).

Capturing the Imperial camp intact, the victors found it well-victualed, a victory feast prepared in advance and awaiting on Tilly’s richly appointed table. Gustavus and his officers dinned in Tilly’s own pavilion, while his army celebrated this titanic victory feasting and drinking from Imperial stores.

AFTERMATH

When news of Breitenfeld reached Vienna, the Imperial court was “thunder-struck”. This was the first battle victory by Protestant forces since the 30 Years War had begun in 1618. Throughout the Protestant world there was rejoicing with a fervor that knew no bounds. At last a champion had appeared, in the form of the “Lion of the North”, and a hopeless cause had been restored.

In Halle, Tilly could rally a mere 600 foot. Pappenheim joined him, with just 1,400 horse remaining under the Imperial banner. Worse news soon followed, as word came that Gustavus’ forces had overrun Merseburg, and after a brief skirmish forced the surrender of another 3,000 Imperial troops. The battle was a disaster for the Catholic cause, and overnight the Imperial army that had brought Germany to its knees ceased to exist.

Breitenfeld was that rare thing: a decisive battle. It utterly changed the tide of a war that had seemed all but over, following 13 uninterrupted years of Catholic-Imperial victory. The 30 Years War would drag on for another 17 years, claiming the lives of both Gustavus and Tilly (and, ultimately, Tilly’s successor, Wallenstein) and countless others, soldiers and civilians alike. But Breitenfeld accomplished the succor of the Protestant movement in Germany; and it was never again close to extinction, as it had been before the battle.

The battle accomplished one other thing as well, and this perhaps not to the benefit of the German people. It prevented an early unification of Germany under Hapsburg rule. It would take another two-and-a-half centuries and the genius of Otto Von Bismarck to achieve that goal.

Militarily, Gustavus ushered in the era of linear formations and firepower as the decisive factor in battle. His infantry, fighting in lines of fewer ranks and greater frontage, allowed less men to cover more ground, and to deliver a greater volume fire to greater effect. Though the pike would continue in use among infantry till the early 18th century, the ratio of pike-to-shot would continue to shift towards firearms; till the invention of the bayonet allowed every infantryman to be both pikeman and musketeer.

In the artilleryman’s art Gustavus was both visionary and revolutionary. He was the first to make good use of light, mobile field guns in battle. In the future all European powers would experiment with and develop this arm. Eventually it would lead to mobile “horse gun” batteries, and more and greater field artillery in every army. Before Gustavus artillerymen were military contractors, hired by generals and princes for each campaign. After Gustavus, they were all military professionals, a branch of every nation’s armed forces.

Breitenfeld solidified Gustavus Adolphus’ reputation as a commander. Though he lost his life a mere fourteen months later at Lützen , he would forever be rated, by such experts on the subject as Napoleon and Clausewitz, as one of history’s greatest commanders.

(For more on Gustavus Adolphus and other leaders mentioned in this piece, see my article, “The 25 Greatest Commanders of the Renaissance“.)

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

NOTES:

- Some scholars of the battle say Pappenheim’s assaults on the Swedish right were impetuous and launched either without Tilly’s sanction or at least prematurely. That Tilly meant to wait on the defensive till reinforcements joined him. Scholars to this day puzzle over what Tilly planned; but as neither Tilly nor his lieutenants penned an account of the battle, we can only speculate. Some have suggested the old Walloon soldier planned an audacious double envelopment maneuver; using his qualitatively superior cavalry to break both wings of his enemy’s forces; while their center was pinned in place by the mass of his infantry, and with the artillery of both sides still pounding away at each other. This may well be the case: Pappenheim’s massive heavy cavalry attack initially on the Swedish right-wing cavalry is reminiscent of Hannibal’s opening gambit at the Battle of Cannae. There, the Carthaginian heavy cavalry led by Maharbal thundered against the Roman left wing horse; shattering them and sending them fleeing from the field. But Gustavus was no Varro (the ill-fated Roman commander at that ancient debacle); and he had an effective counter to Pappenheim’s impetuous assaults.

Some of the artwork in this article has been reproduced with the permission of Osprey Publishing, and is © Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

www.ospreypublishing.com

Pingback: A GUIDE TO DEADLIEST BLOGGER POSTS | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: MOST “BADASS” MILITARY UNITS OF ALL TIME | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page