Long before George R.R. Martin penned his tale of war, intrigue and treachery the ancient world was scene to its own version of The Game of Thrones.

When Alexander the Great died in Babylon 323 BC he left no heir and successor to rule the greatest empire the world had yet seen. While both of his wives (Roxane the daughter of Oxyartes of Bactria; and Stateira , daughter of Darius) were pregnant, he had as yet no legitimate children. His former mistress Barsiné had a son named Heracles, who some claimed was Alexander’s. But Alexander had never acknowledged the boy. Nor had the king made provision for what was to happen in the case of his death. For a ruler who habitually took unnecessary risks, literally leading his army from the front, this was particularly irresponsible. But it was completely in character for Alexander, who ever refused to acknowledge his own mortality.

This bust of Alexander by Lysippos, now in the Lovre, portrays the conqueror in his last years. Lysippos was Alexander’s favorite sculptor, and this is considered his best likeness

The decision of who was to succeed the dead conqueror was thus placed into the hands of the Macedonian army, who by the traditions of their homeland had the sole right to select their ruler. But the generals who led them dictated events, and they soon fell out with each other.

Alexander’s Diadochi (“Successors”) as they came to be called spent the next 40 and more years, from the first squabbles in Alexander’s death chamber to the Battle of Corupedion in 281 BC, attempting to settle the issue by intrigue and force of arms.

The stage upon which the drama that followed played out was vast indeed: stretching from the Pindus Mountains to the Hindu Kush; from the Bosporus to the Nile River. Roughly speaking the struggle was between the forces of the “dynasts”, the satraps and generals who sought to carve up for themselves a portion of the empire as their personal demesne; against those representing a central authority seeking to hold the empire together. This latter was represented until 316 by various Regents for the Kings; and from that year till 301 by Antigonus Monophthalmus, who sought to make himself sole ruler. (Arguably, this cause was taken up late in his life by Seleucus Nicator, who after Corupedion found himself in the same place as Antigonus in 316; and may have, briefly, entertained the same ambition.)

THE PLAYERS TAKE THE STAGE

The leading men present at Babylon that summer of 323 BC and in attendance at Alexander’s death-bed all bore the title of “Bodyguards” (Somatophylakes). This was less a job description than an honorific, meaning men trusted by the king with his life. Traditionally there were seven of these, but that number was raised (temporarily) to eight during Alexander’s campaign in India. Some had commands in the army, or governorship of provinces. They all functioned effectively as Alexander’s Field Marshals and “high command”, and were frequently given independent commands.

The generals gather in the royal bedchamber as Alexander lays dying

First among those at Alexander’s death bed was Perdiccas son of Orontes, the senior Hipparch (cavalry leader) and Alexander’s acting Chiliarch (Vizier). He was a prince of the House of Orestis, one of the petty-kingdoms which comprised the original Macedonian kingdom. At the storming of Thebes in 335 B.C. he had been a battalion commander of the phalanx (pezhetairoi), and was the first to penetrate into the city, where he was wounded. He commanded one of the six brigades (taxis) of the phalanx in all three of the great battles against the Persians. On the eve of the invasion of India he was made one of the Somatophylakes, as well as Hipparch of one of the five original Hipparchies (1,000 man cavalry brigades) into which the Companion Cavalry were reorganized.

Actor Neil Jackson portrayed Perdiccas in 2004’s “Alexander”

After the death of Hephaistion he became the senior officer in the army, taking over the dead man’s duties as Chiliarch. As Alexander was dying the conqueror allegedly gave Perdiccas his signet ring. This was interpreted by most present as nominating Perdiccas as regent for his son(s) yet unborn. He is portrayed in the sources as arrogant and imperious, and could be both cruel and ruthless when necessary. His high-handedness soon put him at odds with most of the other leaders, and alienated him from the common soldiers.

Ptolemy son of Lagos was one of Alexander’s most popular commanders and a possible half-brother (it was rumored that Philip II was actually his real father, though this could well have been Lagid propaganda). His family was from Eordaea in the Macedonian highlands; and he was one of Alexander’s boyhood “Companions”, tutored along with the young prince by Aristotle. He was one of several of Alexander’s friends to be banished by Philip in 337 BC, considered a bad influence on (or too loyal to) the prince. He returned to Macedon only after Philip’s assassination.

He was a junior officer early on and had no command before Gaugamela. Ptolemy accompanied Alexander during his journey to the Oracle of Ammon Ra at Siwa, where the latter was proclaimed a son of Zeus/Ammon. He was later entrusted with an elite force of 5,000 men tasked with bringing Bessus, the murderer of Darius III, back to face the King’s justice in 330 BC. By the invasion of India he was appointed as one of the Somatophylakes, as well as one of the five Companion Hipparchs. He served with distinction throughout the Indian campaign, playing a key role in taking the Rock of Aornus. His Hipparchy was with Alexander on the right-wing at the Battle of the Hydaspes. He was wounded later that year at Harmetelia, a town of the Brahmins, by a poisoned weapon. Though near death, he was personally nursed back to health by Alexander himself.

At Susa he was given as bride Artakama, the daughter of Artabazus of Phrygia and sister to Alexander’s former mistress Barsiné and a relative of the Persian Royal Family. Even-tempered and more modest in his ambitions (and in his manner) than most of his colleagues, he was popular with the rank-and-file Macedonian soldiers. He has the distinction of being the only one of the leading Diadochi to die, peacefully, in his own bed.

Leonnatus was related to the royal house (through Philip’s mother) and had served honorably throughout Alexander’s campaigns. After Issus he was sent to meet and reassure the captured Persian royal women of Alexander’s good-will and intentions. He was elevated to the rank of Bodyguard upon the death of Arybbas in Egypt in 332 BC. He tried to restrain Alexander during his murderous argument with Black Cleitus, and later informed him of the Page’s Conspiracy. He fought beside Alexander inside the Malli/Mahlava fortress of Multan, where Alexander was struck in the chest by an arrow and nearly killed, and defended the fallen king alongside Peucestas till help arrived. During the struggle he was wounded badly in the neck, and nearly succumbed. During the return from India he was left temporarily in southern Baluchistan to pacify the population, at task at which he proved successful. He was flamboyant and ambitious, with ambitions to gain the throne through marriage alliance with the Royal House.

Artist’s conception of one of the seven Macedonian Somatophylakes, the inner circle of generals who comprised the “high command” of Alexander’s court and army

The other Somatophylakes/Bodyguards had less prestige and sway with the army.

Little is known of the background and early career of the Bodyguard Peucestas. Not even his father’s name is mentioned in the sources. An officer named Peucestas son of Macartus was appointed to command the troops left to garrison Egypt in 321 BC. Though scholars always assume this to be a different individual, it is possible that he is one-and-the-same as the future Bodyguard. We know that Peucestas was from the town of Mieza, where Alexander and his boyhood Companions were taught by Aristotle. It is tempting to assume that Peucestas was among these, as it is unlikely that he rose as high as he did in Alexander’s service without being one of the King’s inner-circle of Companions; most of which were boyhood friends.

By the Indian expedition (if not before) Peucestas was appointed as Alexander’s Shield-bearer, a sign of both the trust the King had in him and of Peucestas’ reputation for valor. In this capacity he bore the Sacred Shield (supposed to be that of Achilles, forged by the gods for the hero), taken by Alexander from Troy at the start of his war against Persia. At the fortress of Multan Peucestas (along with Leonnatus) warded the fallen King, suffering himself from javelin wounds. Afterwards he was rewarded by being made an unprecedented eighth Bodyguard.

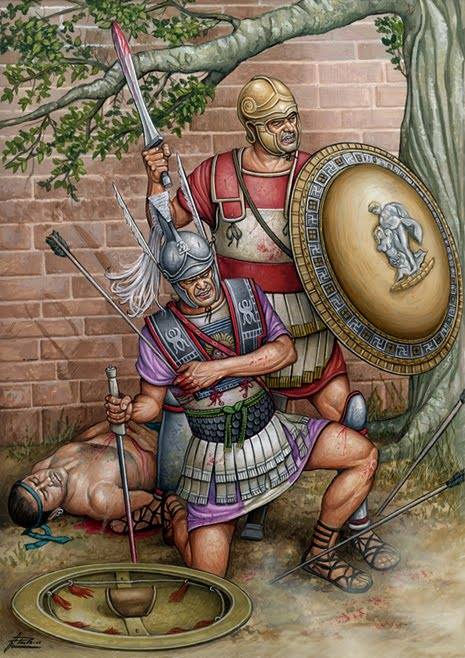

Peucestas, carrying the “Sacred Shield” taken from Troy, wards the wounded Alexander at Multan

Peucestas was appointed satrap of Persis (the Persian homeland) after the return from India. He carried out Alexander’s policies of harmonizing with the native population, wearing Persian robes and getting on well with his Persian subjects. For this he was somewhat derided by the more traditional-minded Macedonians. Near the end of Alexander’s life he arrived in Babylon with 20,000 Persian youths trained as Macedonian phalangites (the pike-armed heavy infantry of the phalanx). He was in close attendance upon the King throughout his fatal illness. Peucestas was obviously a great admirer (nee sycophant) of Alexander’s, and carried out his pro-Persian policies more faithfully than any other Macedonian. He certainly seemed to think himself the best man to carry on the great man’s legacy; a certainty not shared by his colleagues, who held him in much less regard then he had for himself.

Peithon son of Crateuas, was (like Ptolemy) from Eordaea. What he had done to earn his position is largely unknown, but by India he was one of the Bodyguards. He was ambitious and ruthless. Originally aligned with Perdiccas, he entertained ambitions over the eastern (“Upper”) satrapies. Eventually he became and uneasy ally of Antigonas in his struggles against Eumenes.

Lysimachus son of Agathocles was of Thessalian origin, his father perhaps one of the “new men” who came to serve Macedon during Philip’s reign. He may have been one of the young “Companions” of Alexander’s youth tutored along with the prince by Aristotle at Mieza. Few of these childhood friends and fellow students are known by name, but this would explain the position of trust into which Lysimachus was placed in the king’s entourage. In Syria Lysimachus killed a lion single-handedly while hunting with the king, being badly wounded in the process but perhaps saving Alexander’s life. This may have been why he was elevated to the position of Bodyguard. In Sogdiana he was beside Alexander at another such hunt in which Alexander slew a lion. He was a man of great physical strength, easily offended and slow to forgive. He grew cold and cruel in later life. Politically he was a cautious overachiever.

Lysimachus, the future King of Thrace and one-time Bodyguard of Alexander’s. While ultimately one of the most successful of the Diadochi, he was also perhaps the most “prickly” of temperment.

Though Aristonous son of Peisaeus had been a Bodyguard since Alexander’s accession, little is known of him. He is alternately identified as a man of either Pella (the capital) or of Eordaea; which may mean his family hailed from the latter, while he was born and spent his youth at court, perhaps originally as one of Philip’s Royal Pages. He may have been the man who took Alexander’s sword away early in his drunken and ultimately murderous argument with Cleitus. The Roman historian Quintus Curtius has him as one of the men who defended the fallen Alexander in the Mallian fortress, but this is contradicted by Arrian. In the struggles to come he showed no personal ambition, siding always with the Royal House and its regent.

Not present at Babylon were three other men of great importance. One was Alexander’s most trusted subordinate commanders (after the now dead Hephaistion), the other two aging generals of his father Philip, not in Alexander’s inner circle but whose names and reputations among the soldiers cast a broad shadow.

Craterus son of Alexander, a nobleman of Orestis in highland Macedonia, was on the way to Macedon with 10,000 discharged veterans when word came of the King’s death. No man in the army had a higher reputation or was more respected (only Ptolemy was better liked by the troops). He was handsome, affable, and possessed of a natural dignity and strength of character. As noted, he was second only to the now-dead Hephaistion in Alexander’s confidence, and enjoyed the highest commands in the later campaigns; taking Parmenion’s place as Alexander’s chief subordinate commander. He led one of the six brigades (taxis) of the phalanx in all of the great battles against the Persians. His taxis was ever entrusted with the most dangerous and vital position, holding the far left flank of the phalanx at both the battles of Granicus and at Gaugamela. In Bactria he was promoted to be one of the five original Hipparchs of the reorganized Companions. At the Battle of the Hydaspes he commanded the camp and that portion of the army left on the other side of the river, with orders to cross over when Porus was engaged by Alexander’s force. On the return from India, he was entrusted with most of the army and much of the baggage; marching safely along a more northerly route than the one Alexander took though the terrible Gedrosian desert. At the mass wedding at Susa in 324 BC, where Alexander married Stateira the daughter of Darius III, Craterus was only behind Hephaistion and the king in the line of Macedonian officers to be wed. He was given the redoubtable princess Amastris, the niece of Darius as bride. Just prior to the King’s death, he was sent back to Macedon to assume Antipater’s duties as the king’s viceroy in Macedon and Greece, escorted by 10,000 discharged veterans returning home. He had only reached Cilicia when news came of Alexander’s death.

At the Susa wedding in 324 B.C., Alexander married Statiera, the daughter of Darius; while another 500 Macedonians took Persian brides. Craterus was the third to be married, behind only the king and Hephaistion. While most of the leaders put off these wives after Alexander’s death, Seleucus notably remained married to and beget a dynasty upon Apama, daughter of Spitamenes

So great was his reputation and the trust Alexander was known to have placed in him that a story sprang up, related by Diodorus, that with his last words Alexander had actually meant to name Craterus as regent of the empire. According to this story, Alexander was asked on his deathbed to whom he bequeathed his kingdom? He whispered to those assembled, “tôi kratero”: to Craterus (Kratero). But, the story goes, the ambitious men gathered around the deathbed in Craterus’ absence chose to hear the King’s utterance as “tôi kratistôi“: to the strongest. If Craterus ever heard this story, he appears to have put no store on it; and served where he was needed without pressing any special claim to power. Had he indeed been given the regency upon Alexander’s death, it is tempting to think he might have possessed the prestige and ability to hold the empire together.

No man was more trusted by Philip II than Antipater son of Iollus. He was possibly a distant relative of the Royal House, and though nothing is known of his early years from 342 onward he was Philip’s chief lieutenant. That year Philip left Antipater in charge as his regent (viceroy) in Macedon while he campaigned in Thrace for the next three years, extending Macedonian control to the Black Sea coast. Antipater sent troops to Euboea to oppose Athens’ attempt to install ant-Macedonian governments. After the Macedonian victory at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, Antipater was sent with the young Alexander as co-ambassador to Athens to negotiate a peace treaty and return the bones of the Athenians who had fallen in the battle. During Alexander’s reign he was entrusted again with the regency of Macedon, as well as general (strategos) of Europe. He had a difficult job, supplying his king with fresh drafts of men while maintaining Macedonian domination over Greece. When in 331 BC the Spartans, supplied with money and mercenaries by Persia, rose against Macedonian hegemony. Antipater defeated them and killed their king, Agis III at the Battle of Megalopolis. He came into frequent conflict with the Queen Mother, Olympias, who felt she should have been her son’s regent in Antipater’s place. In the coming years, she was his most bitter enemy.

Olympias, lovely but ruthless mother of Alexander; and bitter opponent of Antipater the Regent

In his last days Alexander decided to recall Antipater to Babylon, and replace him as his commander in Europe with Craterus. The king’s death (of which Antipater and his sons were accused of being complicit: see below) forestalled this change of command.

Antipater was physically a small and unattractive man. He carefully planned against future contingencies, and played politics like a chess game; setting up his pawns and moving his pieces with great foresight. He had a brood of ten children, three of which were daughters. He used these to advantage in making marriage alliances with many of the powerful men who would dominate the stage in the coming years. All three daughters would be the wives of future “Successor” kings.

After Antipater, perhaps the most senior officer of Philip’s generation still serving was Antigonus One-Eyed (Monophthalmus). Little is known of his early life, and even the social status into which he was born is disputed. His father was one Philip of Elimeia, one of the highland regions of Macedonia. But while some suppose him to have been a nobleman, there is a tradition that Antigonus was of yeoman-farmer stock. If his humble origin is accepted this goes far to explaining why he is largely unheard of during Philip’s reign and is relegated early in Alexander’s Persian War to holding the satrapy of Phrygia. He is always described as a “general” of Philip’s; though no independent campaign or chief command is credited to him. It is tempting to speculate that during Philip’s reign he likely started his career as a ranker in the either the phalanx (pezhetairoi) or the newly created hypaspists (perhaps even the Agema, or Royal Guard, battalion); and that he rose in rank due to his reputation as a soldier and his renown as a great warrior (he was a notably large and powerfully built man). We have no knowledge of who served as Somatophylakes under Philip II, or held prestigious junior positions such as commander of the Agema of the Hypaspists. Possibly Antigonus rose to one such position prior to Alexander’s reign, though it is doubtful he was one of the Bodyguards, as he was not among Alexander’s original seven, whose identities are known and most of whom were retained-over from Philip’s reign.

Antigonas, as a young soldier during the reign of Philip, and as an aged veteran at the start of the Diadochi Wars (here portrayed by actor Sean Connery)

At the Battle of Granicus he commanded the Greek Allies. After Alexander rolled-up western Asia Minor (Antigonus receiving the submission of Priene), he was left to hold Phrygia with (initially) 1,500 mercenaries, and tasked to keep open Alexander’s line of communications with Macedonia. In this capacity he fought three battles against and ultimately expelled a pro-Persian force; which may have included or even been wholly composed of Greek mercenaries, refugees from the defeat at Issus. It is a testament to his ability and reputation among the Macedonians that despite taking no part in the glories of Alexander’s conquest of the east he very soon made himself a key player in the drama unfolding. The savagery he occasionally displayed (all the more striking when contrasted against his personal affability) may have emanated from years of frustrated ambition and resentment at being “put out to pasture” by Alexander, while younger men garnered the laurels of victory. He was 58 years old when Alexander died in Babylon, but like the Macedonians in general he retained great vigor late into his life. Amidst the chaos soon to unfold he was given ample chance to prove his merit as a soldier and commander; an opportunity he was not to squander.

Lesser figures destined to play key parts stood initially off stage, waiting their opportunity.

Seleucus son of Antiochus had commanded the elite Hypaspists in India. He was roughly the same age as Alexander, born within two years of the prince. His father was an officer of Philip’s, though no record of his accomplishments exist. As a teenager Seleucus served in the Royal Pages (Basilikoi Paides) in Philip’s service, as did many of the sons of the nobility. A story was later told that on the eve of his departure on Alexander’s Persian expedition his father told him that he was really the son of Apollo; that a distinctive anchor-shaped birthmark (which subsequent Seleucid monarchs bore as well) so marked him. The anchor later became a symbol of the Seleucid dynasty.

Seleucus son of Antiochus, though not in the top-tier, would become the most successful of the Diadochi

His position(s) throughout Alexander’s Persian War is unknown. But he apparently served with distinction, because on the even of the Indian Expedition he was given command of the elite Hypaspists brigade. (The Hypaspists were issued silvered shields at the start of the Indian Campaign, and are henceforth increasingly called the Argyraspides, “Silver Shields”.) In this capacity he fought at close-quarters against Porus’ elephants at the Battle of the Hydaspes, an experience that impressed him greatly. In later life he would go to some lengths to procure as many of these huge beasts as he could for his own use.

Seleucus followed Alexander through the ordeal of the Gedrosian Desert. At Susa, he was married to his mistress of several years, Apama, daughter of the Sogdian noble Spitamenes (the most effective of Alexander’s opponents). Unlike most of the other Macedonians who took Persian brides at Susa, Seleucus remained married to Apama throughout her life. He was apparently strong enough to grapple a bull by the horns; and more mild tempered and merciful than perhaps any of the great Successors of Alexander. As commander of the Foot Guard (the Hypaspists, now called the Argyraspides), he was at Babylon attending the King when Alexander died.

Seleucus was with Alexander during the terrible ordeal of the Gederosian desert. Here Alexander refuses a drink of precious water, as there was not enough for more than just himself: if his army could not drink, he would not either. By sharing their privation he cemented their loyalty

Eumenes of Cardia, Alexander’s secretary, was also in attendance at the royal palace. Originally one of Philip’s “New Men”, he was twenty when he became personal secretary to the king in 342 BC. He continued to serve Alexander in this capacity throughout the conqueror’s life. Alexander came to trust him completely, using him on diplomatic missions and eventually, in India, entrusting him with a military command. At Susa he was honored by being given for his bride Artonis, sister to Alexander’s former mistress, Barsiné the daughter of Artabazus (also sister to Ptolemy’s bride, Artacama). After Hephaistion’s death and Perdiccas’ elevation to the dead man’s duties, Eumenes was given command of his Hipparchy, still another sign of Alexander’s confidence in his potential ability as a soldier. Its was a confidence not misplaced.

Eumenes was an able diplomat and shrewd manipulator of men and events, the consummate “clever Greek”. But he always labored under the disadvantage of not being Macedonian, and that he was seen first-and-foremost as a man of letters rather than as a soldier. For the first he was despised by many of the Macedonian officers, for the second he was derided. Neoptolemus, who seems to have harbored a particular animus against him, scornfully remarked that he (Neoptolemus) had followed the king with shield and spear, but Eumenes with only pen and paper. While the more fair-minded realized how unjust this statement was and scoffed, it reflects a lingering derision of Eumenes shared by many. However, he had the trust of Perdiccas, which he retained and used to good advantage throughout the latter’s life. As a Greek outsider whose position was dependent on the patronage of the throne, he was always loyal to the Argead dynasty and to Perdiccas as regent.

When given the opportunity of independent command he showed exceptional ability. It is tempting to speculate that during the conqueror’ life he served not merely as Alexander’s scribe, but as a kind of “Chief of Staff” as well; operating in the same capacity as Marshal Berthier vis-à-vis Napoleon. This might explain in part the skill he showed later in maneuvering armies: there can have been no better school of command than to have served at Alexander’s side.

Though he was destined to play an important role in the coming struggle, Cassander son of Antipater began “the Play” distinctly off-stage. It is uncertain if he was the first or second son of Antipater (his brother, Iollus, bore the name of their paternal grandfather, usually given to the eldest son). A child-hood Companion of Alexander’s, he too was educated by Aristotle at Mieza; and in fact maintained a life-long correspondence with his former teacher. That he was left behind in Macedon with Antipater when all of Alexander’s other child-hood Companions accompanied the King to Asia is one of many signs that the two men shared a mutual distaste, if not downright loathing of each other.

Cassander likely fought beside his father at Megalopolis in 331 BC, though there is no record of his participation (details of the battle are lacking in any case). In 323 he came to Babylon to plead his father’s case when Antipater was recalled, accused of malfeasance. In the king’s audience hall Cassander openly sneered at Alexander’s and some of the Macedonians of the court (such as Peucestas) wearing Persian robes. When he saw noble Persians performing their customary proskynesis (full prostration, forehead to the ground) before Alexander, Cassander broke into scornful laughter. Proskynesis had been a sore subject among the Macedonians, only recently resolved (Persians would continue to perform it, as was their custom; while for Macedonians and Greeks it was voluntary). This sudden outburst, which in effect poured salt into a freshly healed wound, so enraged Alexander that he leapt from his throne; and grabbing the startled Cassander, smashed his head into the floor, perhaps forcing him to perform the proskynesis! The shocked and infuriated Cassander did not linger at Babylon, instead returning post-haste to Macedon.

Cassander, portrayed by Jonathan Rhys Myers in 04’s “Alexander”. Though the film erroneously depicted him accompanying Alexander on his campaigns (he stayed in Macedon with his father, Antipater), Rhys Myers was sufficiently reptilian in his portrayal of the cold-blooded Cassander

A story grew-up a few years later (likely spread and perhaps started by Olympias, Alexander’s mother) that the true purpose of Cassander’s visit to Babylon was to bring poison to kill the King. According to this story the plot was hatched by Antipater; who feared being removed from his position of authority as Regent in Macedon, and being called to account for his administration. (Alexander had recently executed Macedonian governors who’d abused their power and his trust while he was away in India. Perhaps Antipater feared a similar fate.) Cassander supposedly brought poison in the hollowed-out hoof of an ass; and that the poison was contaminated water. This “poison” was then given to Cassander’s brother, Iollus, the king’s Cup Bearer; who then introduced it into Alexander’s wine during the fateful party of Medius’.

The truth of this story can never be known, of course, but it is now, and was then, plausible. It gained wide circulation and credence in the years of struggle that followed. Considering the bloody-handed actions taken by Cassander against the House of Alexander, it is certain he bore a deep and burning hatred for the man he was accused of murdering, and was unscrupulous enough to have carried out the deed. Of all the Diadochi, as ruthless a collection of rivals as ever existed, Cassander stands out as the most deliberate, cold-blooded, and murderous of them all.

Polysperchon son of Simmias was of the older generation who’d soldiered under Philip. From Tymphaia on the border with Epirus, he gave good service throughout Alexander’s campaigns. He was a Taxiarch commanding a brigade of the phalanx at Gaugamela, and continued in this capacity during the Indian expedition. He was one of the “old timers” discharged and returning with Craterus to Macedon when news arrived of the king’s death. Throughout the troubles to come he doggedly served the regent and the central authority. While he was successful for a time in the “limelight” as an independent actor, his lack of integrity and judgment eventually pushed him off the stage in favor of stronger (and wiser) characters.

Like Polysperchon, Meleager son of Neoptolemus was of the older generation who’d fought in Philip’s wars. He too commanded a taxis (brigade) of the phalanx throughout Alexander’s campaigns. Despite such long service, Alexander did not promote him to any higher command, or entrust him with any special assignments. From this we can deduce that he was a competent if unimaginative soldier. He was much respected by the rank-and-file of the Macedonian infantry as a “crusty old salt”. He was one of them, and like them he was disgruntled at the “Medizing”[1] of Alexander and some of the officers of his court. Following the King’s death, he soon became spokesman for the common soldiers of the Macedonian infantry at Babylon.

The Macedonian phalanx, heart of the army. At Babylon their spokesman was crusty old Meleager

Neoptolemus (his father’s name is not given in the sources) was related to the Epiriot royal house, and so was likely a kinsman of Alexander’s on his maternal side. He may have come to Macedon as a boy along with Olympias’ brother, Alexander of Epirus; and like this prince might have served as a Royal Page (Basilikoi Paides) at Philip’s court. At some point he became Alexander’ “Armor Bearer”, an honor whose duties (if any) are unknown. He commanded the Agema of the Hypaspists after the death of Nicanor son of Parmenion. He gained the distinction of being the first man up the ladders at the storming of Gaza. He was arrogant and untrustworthy, and had a particular animus against Eumenes; the exact cause of which we can only speculate. His exact rank and position when Alexander died is unknown, but it was sufficiently high that he would be given command of a satrapy (province). He was hot-headed, brave, and spiteful. When all was said, he displayed little aptitude for leadership. His memory, however, may suffer from a bias in the sources: our chief historian of the period, upon whom most other’s rely was Hieronymus of Cardia, a kinsman of Eumenes, his enemy.

Nothing much is known from the sources of the background of Antigenes the Taxiarch (not even the name of his father). He served under Philip at the siege of Perinthus in 340 BC, losing an eye. He is next mentioned in 331 BC, placing second in the games at Sittacene. On the eve of the Indian invasion he was elevated to command of the crack phalanx taxis previously commanded by Coenus (who was promoted to the rank of Hipparch of the Companions). In this capacity Antigenes’ command was given pride-of-place on the right of the line, beside the elite Argyraspides (commanded by Seleucus) at the Battle of the Hydaspes. In this position he was engaged in hard fighting against Porus’ elephants and infantry. As commander of the senior taxis of the phalanx, he was perhaps second only to Seleucus among infantry commanders. Like many of Alexander’s veteran soldier’s in Babylon that summer, Antigenes was filled with resentment at the way Alexander had given equal preferment to and adopted many of the ways of the despised Persians. Like them he expected a larger portion of the spoils of victory after Alexander’s death than he (and they) had received during the conqueror’s life.

The stage was thus set for the titanic drama about to unfold. The players stood ready, each of the leading characters ambitious to obtain the “starring” role, the supporting cast eager to move-up to leading roles, and even the bit-players ready to “understudy” their betters and step into their roles should they falter.

NEXT: PERDICCAS TAKES CONTROL

For more, read Great Captains: Alexander the Great

And The 25 Greatest Commanders of the Ancient World

And Granicus, Alexander’s Most Perilous Battle

RECOMMENDED FURTHER READING:

NOTES:

- Medizing: term for Hellenes who adopt Persian ways.

Pingback: GREAT CAPTAINS: ALEXANDER THE GREAT | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: GRANICUS: ALEXANDER’S MOST PERILOUS BATTLE | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: 25 GREATEST COMMANDERS OF THE ANCIENT WORLD | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI: MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 2) | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: ARMIES OF THE SUCCESSOR KINGDOMS: THE PTOLEMIES | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI: MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 3) | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES: PART 3, LAMIAN WAR AND ROYAL WOMEN | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 4): REVOLT IN BACTRIA AND THE LAMIAN WAR | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: SALAMIS: GREECE (AND WESTERN CIVILIZATION) IS SAVED BY THE “WOODEN WALLS” | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 5): THE PLOT THICKENS | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: MAD KINGS AND MACCABEES: THE FIRST HANUKKAH | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 6): AMAZON QUEENS AND STOLEN CORPSES | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 6): AMAZON QUEENS AND STOLEN CORPSES | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 7): PERDICCAS INVADES EGYPT | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 8): EUMENES AND CRATERUS | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 9): SETTLEMENT AT TRIPARADEISOS | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: MAD KINGS AND MACCABEES: THE STORY BEHIND THE FIRST HANUKKAH | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Dear Deadliest Blogger-

I posted today on the Diadochi and I chose your blog to link to. While the thrust of my page is talking rabbits, I love dragging ancient history into the light of day. Your article is excellent and the best I found on the subject. Of course, if you do not wish to be associated my unstable, drunken, delusional, vain, probably psychotic and certainly out of control bunny then tell me and I will take the link down. Hail Hydra!

That is fine, Billy Bunny!!

Many Thanks. I just read last night your article on the conquest of Baghdad. I am reminded of what Machiavelli had to say about gold being the sinews of war. Keeping a hoard of money is keeping it safe for those who conquer you. I am an obsessive reader of history and I am amazed at how much is out there I have never heard about. I also think that Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck did more with less than any other commander in history, just thought I’d toss that in.

Doubtless you have read Ghost on the Throne which is where I found out about Eumenes. I am very happy to find such a good blog (a word I hate) as yours, this allows me to not have to work hard on my own micro-essays.

I grew up watching Bugs Bunny and being spellbound by Jason and the Argonauts, which was shown ad nauseum on T.V. Is it possible that this has influenced me?

Great writing is entertaining. Your work is fascinating.

Best wishes, Paul K Davis

We have very similar tastes, Paul. I loved Jason and the Argonauts as well, Paul. I think it stimulated my love of mythology growing up. But is was several things that did so for history. First was Life Magazine, in the early 60s, doing a series on “The Glory that Was Greece”. I was particularly enthralled with the episode on the Persian Invasions and the Peloponnesian War. Then National Geo did a piece on “In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great”. The illustrations were terrific. Along came “Classics Illustrated” comics, with issues on “Caesar’s Gallic War”. Finally, I saw the 1962 film, “300 Spartans”. Hooked! I’ve loved history ever since, and am now delighted to be able to share my decades of study with you and others who enjoy my reading.

I forgot, here is the link – https://misterscribbles.blogspot.com/

I was a more of Steve Reeves in Italy sorta kid. I just finished Victor Davis Hanson on the subject of Epaminondas and I do not care for Sparta at all. I have always identified with Athens. However, after they executed 8 admirals after Arginusae, I have decided they deserved to lose that awful war. I find the Romans less infuriating and more interesting, and evil than the Greeks as I find it easier to draw parallels between them and us. The games are fascinating. Interestingly enough, Terry Jones wrote an excellent book about the Romans and everyone else entitled Barbarians that was a real eye opener. When someone can use history to show a light on our times then that is a teacher. John Keegan did this with the Mask of Command, comparing our leaders to those of tribal warriors keeping the casualties at exceptable levels.

In The March of Folly, Ms. Tuchman states that as a condition of folly the action taken must have been known to be wrong at the time. I wonder how the U. S. is going to be seen in a 100 years. Because of my innate aggression I try to not interact with anyone concerning politics. When I was doing theater in Austin I said nothing to anyone, giving me a reputation for level headed fairness, ha ha! I guess where I am going with this is that I really think it is a good idea to look before you leap, unless one is in the cavalry.

Your writing impresses me enough that I am going to try harder, although I hardly ever put links in. I like weird stuff that is true. I am preparing a drawing of the Synodus Horrenda, which I just heard about. Now that is a story. I am in the middle of a 15th century Italy craze, and what a cast of characters that is.

Great job with your hair, I also shave my head. With a black turtleneck I feel like an operative of SPECTRE. Please keep up the good work, I enjoy it very much.

Paul Davis

In the above I meant to say that I find the Romans far worse than the Greeks, easy call there. I also meant to write “tribal elders”, not warriors. I have and have read Primitive War by Turney-High and this was really a blunder on my part. This is why I need to proof read more. Please do not feel that you must post my communiques.

Do you have anything on Charles XII of Sweden? I am linking to Wikipedia but I find them stilted and formulaic. I searched your site but did not find what I need.

As always, if I become tedious then please ignore me. Half of my readers are out of Europe although I suspect they are there for the hybrid animal pictures and not my opinion on things I know Jack Nothing about.

It is probably obvious that I am starved for discussion concerning these matters. History is the story of colliding dynamics. Yours,

PKD

Not tedious at all, my friend.

I recommend to you a book by Charles Fair, “From the Jaws of Victory”, by Charles M. Fair. One of the chapters, “The Tiny Lion and the Enormous Mouse” is about Charles XII and the Great Northern War. https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0671209973/ref=dbs_a_def_rwt_bibl_vppi_i0

I just purchased a two volume compendium of articles on the Great Northern War, with plans to write articles on the subject in my blog. I’ve long been a fan of Charles XII, one of the great battle captains of his age. https://www.amazon.com/Great-Northern-War-Compendium-Set/dp/0996455779

Pingback: ALEXANDER TAKES THE FIRST STEP TO GREATNESS AT THE GRANICUS! | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 10): THE REGENCY OF ANTIPATER | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: A GUIDE TO DEADLIEST BLOGGER POSTS | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

Pingback: Il problema della successione ad Alessandro e le prime guerre fra i Diadochi – Studia Humanitatis – παιδεία

Pingback: DIADOCHI – MACEDONIAN GAME OF THRONES (PART 11): THE SECOND WAR BEGINS | The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page